We’ve arranged a global civilization in which most crucial elements – transportation, communications, and all other industries; agriculture, medicine, education, entertainment, protecting the environment; and even the key democratic institution of voting – profoundly depend on science and technology. We have also arranged things so that almost no one understands science and technology. This is a prescription for disaster. We might get away with it for a while, but sooner or later this combustible mixture of ignorance and power is going to blow up in our faces.

—Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World

A recent poll by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute found, as many previous surveys have found, that Americans’ knowledge of political and historical facts about our country is abysmal. But this one added a twist – it surveyed elected officials as well as ordinary citizens, and found that their knowledge of the same facts was, if anything, even worse. (You can take the quiz yourself.)

I’m astounded that elected officials didn’t do better than the average person. This is a worrying development that suggests the pervasive anti-intellectualism in our society is making its way into government. With some of these questions – for instance, the question about which branch of government has the power to declare war – the incorrect answers can likely be blamed on the influence of a right-wing movement that’s actively hostile to the ideas of judicial review and separation of powers. But many of the questions have no such ideological implications, and wrong answers can only be blamed on a more general hostility to empirical knowledge, education and other positive qualities commonly scorned in the media as “elitism”.

Commenters like Susan Jacoby have noted the pernicious effects of dumbing down our civil discourse, making us less able to evaluate the policy choices we face as a democratic nation. But worse than not knowing is the attitude that we don’t need to know – that subjective certainty or ideological dogma can stand in for consensus, empirical knowledge about the way the world works. Religious faith is a special offender in this regard, teaching as it does that authority or tradition is a sufficient reason to believe something, and often praising believers as virtuous for believing things that are contradicted by the evidence. An ignorant, poorly educated society is fertile soil for every kind of superstition. Conversely, less educated people are far more likely to believe in ideas such as miracles, demons, and biblical literalism. (See also.)

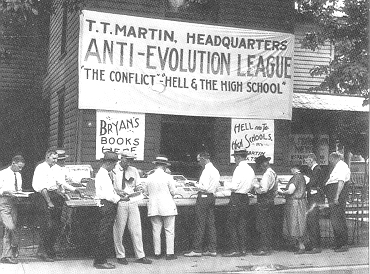

Anti-intellectualism is nothing new, of course. There’s always been a strong undercurrent of it in American society, one that dates back at least to the Scopes trial, and it’s not a surprise that belligerently anti-science regions of the country elect representatives who act in kind. That’s not new, but what is new is that our society – stretching the limits of what Earth’s resources will support – is increasingly dependent on science and technology, and increasingly beset with problems, such as global climate change, that only scientific understanding will give us a hope to comprehend or solve. As the stakes get higher, we can less and less afford to have irrationalism poisoning the public debate and swaying our policy choices. The risk is too great that it will lead us astray at a critical moment.

The problem of anti-intellectualism has no easy solution, particularly when so many people take pride in their ignorance rather than viewing it as something to be ashamed of. Improving public schools is necessary, but at best it treats a symptom rather than a cause. What we need more is a return to the attitude that being intelligent and educated is a good thing which people should aspire to.

This is part of the reason why atheists must take a greater role in public discourse. Religious liberals and moderates can and often do join with us on specific social issues – but even they, for the most part, take the position that faith is an acceptable way of making policy decisions. We have an altogether different message, and one that’s far more vital: decisions that affect the common good must be made on the basis of reason. That’s a message worth promoting, and that’s why we should disregard the squawking of those pundits who urge atheists to keep quiet and not criticize religion, because it’s “disrespectful”. Our message, in the long run, is crucial and necessary; if we need to do damage to established superstitions to get it out, so be it.