In the past few weeks, there’s been a barrage of attacks on the so-called New Atheists, accusing them of inciting bigotry against Muslims or of fostering irrational hatred for Islam. This charge has been laid by Murtaza Hussein on Al Jazeera, Nathan Lean on Salon, and Glenn Greenwald on The Guardian, among others.

In the past few weeks, there’s been a barrage of attacks on the so-called New Atheists, accusing them of inciting bigotry against Muslims or of fostering irrational hatred for Islam. This charge has been laid by Murtaza Hussein on Al Jazeera, Nathan Lean on Salon, and Glenn Greenwald on The Guardian, among others.

Now, it’s true that some high-profile New Atheists have made serious missteps when speaking about Islam. But it’s equally true that New Atheism is a freewheeling, disputatious, leaderless movement with a broad diversity of views, and just because we hold someone in esteem doesn’t necessarily mean we agree with all or even most of what they think on issues other than atheism.

The late Christopher Hitchens, for example, made some bloodcurdling and wholly unacceptable warmongering remarks at a conference in 2007. But the other side of this story – not reported by Hussain, by Lane or by Greenwald – is that the audience was seriously upset, and responded with boos, walkouts, and ferocious criticism. Sam Harris has also faced strong criticism and pushback for some ill-chosen remarks about airport profiling.

On the other hand, some of the statements used to condemn New Atheists have been lifted out of context. For example, Hussein criticizes Dawkins’ remark about “Islamic barbarians,” ignoring the fact that Dawkins wasn’t describing Muslims in general, but a specific group of people: the fanatical fundamentalists who conquered part of Mali last year, burning books and smashing historic Sufi tombs in the city of Timbuktu. The epithet “barbarian” is an appropriate term for people who seek to destroy the relics and records of human history, just as with the Taliban who destroyed the Buddhas of Bamiyan.

Some of the same points hold for Harris. He’s been accused of supporting torture, when in fact he explicitly argues that it should be illegal, even though there are extreme and admittedly improbable ticking-time-bomb scenarios where it might be the only way to obtain information that would save lives. (This is, as he notes, the same position taken by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.) He’s also been accused of cheering the idea of a nuclear first-strike against Islamic countries, when in reality he says this would be an “unthinkable crime,” even if we were compelled to do so as an act of self-defense against a regime of martyrdom-seeking fanatics who acquired a nuclear weapon.

But above and beyond these specific points, the core message of the New Atheists is one that any progressive ought to agree with, namely that no idea is sacred. No belief is above criticism, no matter whether it stems from culture, religion, politics, or science, no matter how old and venerable it is, no matter how many millions of people may believe it or think that questioning it is impolite. The only questions that matter are “Is it supported by the evidence?” and “Is it opposed to human rights?” And if an idea, any idea, fails on both counts, it can and should be thrown out.

Obviously, nothing I say here should be construed as a defense of imperialistic wars against Muslim countries (for the record, both Dawkins and Harris were against the Iraq war). Nor do I seek to justify any policy which entails denying Muslims the same legal and constitutional rights granted to everyone else. But the fact remains that there’s a frightening strain of violent illiberalism in Islam, and often it’s not far from the surface.

As Richard Dawkins points out, Sir Iqbal Sacranie, one of the U.K.’s leading moderate Muslims, favors the death penalty for apostates from Islam (although he says that “it is very seldom enforced,” as if that were a mitigating factor).

Many, even more outrageous incidents come readily to hand. The artist Theo van Gogh, a distant descendant of Vincent, was murdered in the street by a Muslim fanatic for making a film that criticized the treatment of women in Muslim societies. (His friend and collaborator, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, was also targeted and still routinely gets death threats.) When the newspaper Jyllands-Posten published cartoons of Mohammed in a show of support for free speech, there were violent riots around the world, a Danish embassy was bombed, and police have broken up several murder plots against the cartoonists (one of whom, Kurt Westergaard, was attacked at home by a man wielding an ax).

And when the firebrand Dutch politician Geert Wilders made an admittedly inflammatory anti-Islam film called Fitna, the kingdom of Jordan sought to have him extradited so he could be prosecuted for violating Jordanian anti-blasphemy laws. No matter what one thinks about the merits of Wilders’ film, this ought to chill the spine of every free-speech advocate, since it would mean that any Islamic country could exercise a veto over any speech anywhere in the world. When the Netherlands refused to extradite Wilders, the 56-member Organization of the Islamic Conference issued a statement strongly condemning the decision and saying they were “deeply annoyed” by it. The OIC has also been active at the United Nations, pushing hard for international treaties that would outlaw “defamation of religion”.

But it would be misleading to say that the New Atheists are concerned about Western lives above all else. Indeed, what we recognize is that the people who suffer the most from unchecked Islamic fundamentalism are other Muslims (or ex-Muslims). When Islamic theocracies rise to power, it’s their own people they oppress, especially GLBT people and women.

We’ve seen this in Mali and Afghanistan, where a girl was shot in the head for going to school. We’ve seen it in Saudi Arabia, still a cruel theocracy where women are treated as prisoners of men. We’ve seen it in Pakistan, where Taliban incursions in regions like the Swat Valley mean a reign of terror for those living there, and where heroic human-rights advocates like Salman Taseer have been shot down in the street (and mobs cheered his assassin). We’ve seen it in Bangladesh, where a democratic government has arrested atheist bloggers at the instigation of Islamists, who are marching to demand that they be put to death.

We’ve seen it in Egypt, where a nominally democratic government has convicted the atheist blogger Alber Saber of blasphemy, and is prosecuting the renowned satirist Bassem Youssef for “denigrating Islam.” We’ve seen it in the preachers and lawmakers who blame women for the violent sexual assaults committed against them.

We’ve seen this pattern in stable, established democracies as well. In India, angry Muslim mobs have been able to shut down newspapers and get their staff arrested, just for printing editorials in favor of free speech and secularism, by exploiting laws which forbid “acting to outrage religious feelings”. (It should scarcely need saying that laws like this directly incentivize the worst behavior, since they reward people for being irrational and easily angered.) In Indonesia, a soft-spoken civil servant named Alex Aan was beaten and imprisoned for being an atheist. And in Malaysia, the law made it illegal for non-Muslim religious publications to use the word “Allah” under any circumstances, even if that was the correct word for “God” in the writer’s own language. A court ruling which set aside this law under an extremely narrow set of circumstances still provoked rioting, vandalism and firebombing of churches.

As horrendous as all of this is, none of it means that Islam is intrinsically violent in a way that other religions aren’t. (That would be a hard argument to defend, considering that Islam is a theological descendant of Judaism and Christianity, and the Qur’an’s ideas about theocratic monarchy, holy war, hellfire for unbelievers and paradise for the righteous are all based on similar passages in the Bible.)

Rather, it means that at this point in time, at this stage in its historical and cultural development, Islam as a whole hasn’t yet shed the anti-democratic, anti-humanist baggage of its past. Islamic society badly needs an Enlightenment to curb its worst tendencies, just as the historical Enlightenment curbed the worst tendencies of medieval Christianity. The Arab Spring could serve that purpose, but there are worrying signs that religious fanatics are exploiting and hijacking it. And in the meantime, we still have real people suffering under the crush of theocracy; we still have the grave danger of medieval mindsets in control of modern-day weapons.

The New Atheists are speaking out to call attention to this because we care for the welfare of humanity. Contrary to those who assert that culture is immutable and moral progress impossible, we believe that people can be better than this; that if given the chance, they can be persuaded by rational argument to set aside the superstitions that have caused so much unnecessary bloodshed and destruction. We may fail, or we may go astray at times, but I’m confident that the goal at which we aim is a worthy one. Our most ferocious critics ought to consider whether they can say the same, and to ask themselves what end state they’re seeking to bring about.

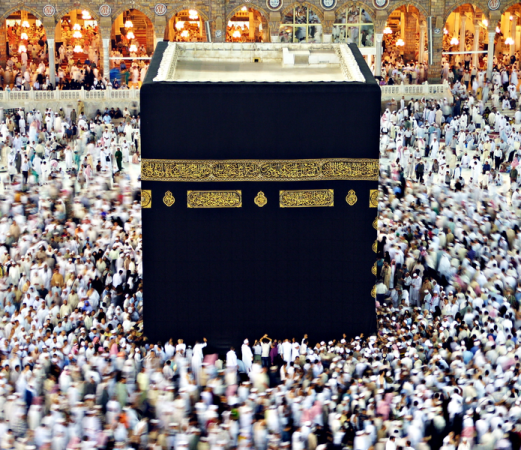

Image credit: Basil D. Soufi, released under CC BY-SA 3.0 license; via Wikimedia Commons