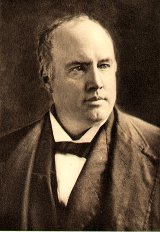

I’ve been reading The Great Agnostic, Susan Jacoby’s biography of Robert Ingersoll, which has only increased my admiration for the great 19th-century freethinker. I knew that, in addition to his tireless opposition to religion, he was a staunch defender of women’s equality, of racial justice and of free speech unconstrained by blasphemy laws, despite living in a time when all of these were radical positions. But Jacoby’s book showed that Ingersoll was an even greater man than I’d thought: he was astoundingly progressive even by today’s standards, let alone the standards of his own era.

For example, even though he moved in exalted social circles and was a friend to some of the most powerful politicians and corporate titans of the Gilded Age, Ingersoll’s sympathies were always with the poor and the working class. Here’s an essay he wrote in 1980 1890 about labor rights, “Eight Hours Must Come“, that could have appeared as an editorial in any newspaper today:

The working people should be protected by law; if they are not, the capitalists will require just as many hours as human nature can bear. We have seen here in America street-car drivers working sixteen and seventeen hours a day. It was necessary to have a strike in order to get to fourteen, another strike to get to twelve, and nobody could blame them for keeping on striking till they get to eight hours.

For a man to get up before daylight and work till after dark, life is of no particular importance. He simply earns enough one day to prepare himself to work another. His whole life is spent in want and toil, and such a life is without value.

Of course, I cannot say that the present effort is going to succeed — all I can say is that I hope it will. I cannot see how any man who does nothing — who lives in idleness — can insist that others should work ten or twelve hours a day. Neither can I see how a man who lives on the luxuries of life can find it in his heart, or in his stomach, to say that the poor ought to be satisfied with the crusts and crumbs they get.

…The laboring man, however, ought to remember that all who labor are their brothers, and that all women who labor are their sisters, and whenever one class of workingmen or workingwomen is oppressed all other laborers ought to stand by the oppressed class. Probably the worst paid people in the world are the workingwomen. Think of the sewing women in this city — and yet we call ourselves civilized! I would like to see all working people unite for the purpose of demanding justice, not only for men, but for women.

All my sympathies are on the side of those who toil — of those who produce the real wealth of the world — of those who carry the burdens of mankind.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons