I’ve been writing a lot lately about hatred and discrimination, about the small prejudices that keep humanity fractured and ignorant. It’s important to fight for reason and equality, but I think it’s equally important to remember why we’re fighting these prejudices, and keep in mind the greater things that we can accomplish if we overcome them. Consider, then, this column about the real meaning of the exoplanet revolution by Caleb Scharf, director of astrobiology at Columbia University.

The early, less sensitive planet-detecting methods were best suited to find “hot Jupiters“, gas giants that orbited their stars at extremely close distances. But our methods have grown more sensitive since then, making it possible to detect the medium-size worlds called “super-Earths“, and even exoplanets the size of the Earth or smaller. Despite the heartbreaking failure of NASA’s Kepler planet-finder satellite, the search continues, and we now know of almost 1000 confirmed exoplanets, with many more likely to be hiding in data yet to be analyzed.

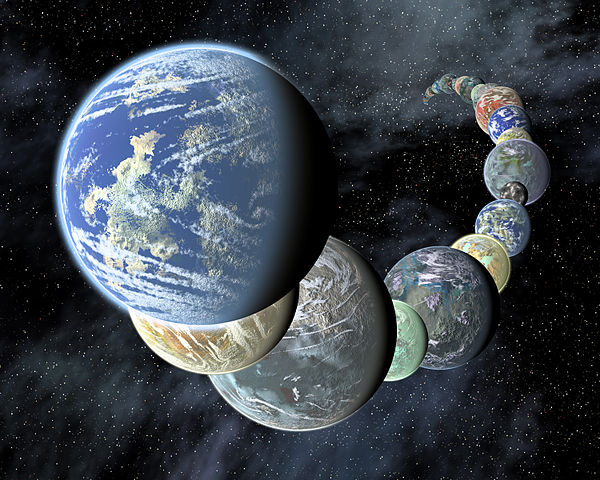

I grant that we’re not yet ready to begin compiling the Encyclopedia Galactica. In most cases, everything we know about these planets is defined by a few numbers: the length of their orbits, their size, their average density, their surface temperatures. For a very few, we have spectrographic evidence for the composition of their atmospheres, hints of the presence of organic molecules; even, in one case, the signature of a raging global superstorm. But we don’t know what they look like. We don’t know whether they have rings or moons; we don’t know whether they have plate tectonics or magnetospheres; we don’t know whether they’re ocean worlds, ice worlds, desert worlds, or temperate worlds with continents and seas.

But the sheer size of the possibilities ought to set anyone’s imagination afire. The most common kind of stars in the galaxy are red dwarfs, smaller and cooler than our sun. There’s every indication that planets orbiting at the right distance from these stars could support life – and there are a lot of them:

The estimated number of Earth-sized planets orbiting around these stars at a distance that allows for the possibility of a temperate surface (capable of holding that biological elixir — liquid water) varies from study to study, but it’s coming in at about one per seven systems. Given the concentration of these small stars locally, there is a 95 per cent probability that one of these potentially temperate worlds sits within a mere 16 light years of Earth. There could be about 23 billion stars in our Milky Way galaxy, each harbouring Earth-sized planets with life-friendly temperatures on their surfaces.

It didn’t have to be this way. We could have found ourselves living in a universe where planets were spectacularly rare, where there was nothing between the stars but clouds of gas and dust. Our solar system could have been unique, the product of a one-in-a-trillion fluke of chance; the human species could have found itself isolated forever, like a castaway clinging to a lone piece of driftwood in an ocean with no islands. Or, we could have found that planets were common but habitable planets were the rarity; the Earth could have been a flourishing green-and-blue exception in a cosmos of boiling gas giants and frozen, airless lumps of rock.

But delusions of our uniqueness have been knocked down every time, and this is just the latest domino in that chain to fall. We have every reason to believe that terrestrial planets like the Earth aren’t the exception, but the rule. (And why not, when the explosion of a single star forges enough heavy elements to create 200,000 planets like ours?) Far from being a rarity, our world might merely be one in an unimaginably rich galactic community of billions like it. And where there are so many planets, how could we not expect that at least some of them harbor life of their own, possibly even minds like our own? Even if the evolution of intelligence is a rarity, we have billions of tumbles of the cosmic dice to work with.

Granted, even if the galaxy is overflowing with sentience, we’re separated by vast gulfs of time and space. Even if habitable planets are common, we’ll probably never jaunt between solar systems like a sailing ship stopping at different ports of call. Space is too big, and physics is too unforgiving. But even if we never have a working warp drive or a convenient wormhole network, it’s far from impossible that we could build robot messengers and surveyors, artificial intelligences that would make the trip to other planetary systems and report back, centuries or millennia later, on what they found.

It’s even conceivable – just barely – that we could build colony ships, multi-generational arks that would be sent on a one-way mission to a hospitable nearby star system. The resources required to construct such a ship would be enormous, and even beyond the technical challenges, the psychology of the people who signed up for the mission would be a major concern. But human beings have always been explorers, and there’s an unimaginable richness of planets waiting to be discovered. Who among us wouldn’t be tempted, even just a little, by the prospect?

Image credit: NASA, via Wikimedia Commons