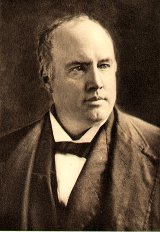

In 1889, a literary magazine called the North American Review solicited essays on the question of whether divorce was ever morally justifiable. Although all the other answers were from clergy (who, for no apparent reason, are always deemed to be the experts on these kinds of questions), they also printed a response by the great American freethinker Robert Green Ingersoll.

As in many other things, Ingersoll’s progressive, humanistic views were decades ahead of his time. He argued that marriage shouldn’t be treated as a transfer of property or a supernaturally decreed state of servitude, but a mutually agreed-upon contract between two free people, one that can and should be dissolved in cases of brutality, neglect, or simply when the love that created it no longer exists. This was in sharp contrast to the religious answers, some of which argued that marriage ought to be indissoluble even if one partner was violent or abusive (one of the respondents, a Catholic cardinal, said that battered women or people trapped in unhappy marriages should pray for “the grace to suffer and be strong”).

Although society has long since come around and this question has been settled in Ingersoll’s favor, his views are still relevant today. Same-sex marriage wasn’t even thought of in the 1800s, but by advancing the idea of marriage as a contractual institution, Ingersoll and his fellow freethinkers overthrew the claim of the churches to be the sole arbiters of how human beings should live and love, and thereby laid the ground for all the moral advances that followed. Here’s what he had to say:

The world for the most part is ruled by the tomb, and the living are tyrannized over by the dead. Old ideas, long after the conditions under which they were produced have passed away, often persist in surviving. Many are disposed to worship the ancient – to follow the old paths, without inquiring where they lead, and without knowing exactly where they wish to go themselves.

…In this contract of marriage, the man agrees to protect and cherish his wife. Suppose that he refuses to protect; that he abuses, assaults, and tramples upon the woman he wed. What is her redress? Is she under any obligation to him? He has violated the contract. He has failed to protect, and, in addition, he has assaulted her like a wild beast. Is she under any obligation to him? Is she bound by the contract he has broken? If so, what is the consideration for this obligation? Must she live with him for his sake? or, if she leaves him to preserve her life, must she remain his wife for his sake? No intelligent man will answer these questions in the affirmative.

…The next question is as to the right of society in this matter. It must be admitted that the peace of society will be promoted by the separation of such people. Certainly society cannot insist upon a wife remaining with a husband who bruises and mangles her flesh. Even married women have a right to personal security. They do not lose, either by contract or sacrament, the right of self-preservation; this they share in common, to say the least of it, with the lowest living creatures.

This will probably be admitted by most of the enemies of divorce; but they will insist that while the wife has the right to flee from her husband’s roof and seek protection of kindred or friends, the marriage – the sacrament – must remain unbroken. Is it to the interest of society that those who despise each other should live together? Ought the world to be peopled by the children of hatred or disgust, the children of lust and loathing, or by the welcome babes of mutual love? Is it possible that an infinitely wise and compassionate God insists that a helpless woman shall remain the wife of a cruel wretch? Can this add to the joy of Paradise, or tend to keep one harp in tune?

…The ground has been taken that woman would lose her dignity if marriage could be annulled. Is it necessary to lose your liberty in order to retain your moral character – in order to be pure and womanly? Must a woman, in order to retain her virtue, become a slave, a serf, with a beast for a master, or with society for a master, or with a phantom for a master?

…Marriages are made by men and women; not by society; not by the state; not by the church; not by supernatural beings. By this time we should know that nothing is moral that does not tend to the well-being of sentient beings; that nothing is virtuous the result of which is not good. We know now, if we know anything, that all the reasons for doing right, and all the reasons against doing wrong, are here in this world. We should have imagination enough to put ourselves in the place of another. Let a man suppose himself a helpless woman beaten by a brutal husband – would he advocate divorces then?

Ingersoll closed his essay with a rhetorical flourish I can’t overlook, one whose relevance is unfortunately obvious even today:

When the world is civilized, no wife will become a mother against her will. Man will then know that to enslave another is to imprison himself.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons