The Civil Rights Act is an abiding dilemma for members of the right-wing Church of Not Gay. As marriage equality continues to progress, their latest cause celebre is arguing that believers should have the right to refuse service to gay couples – whether they be photographers, bakers, owners of wedding venues, even county clerks – all in the name, supposedly, of “religious liberty”, which they believe should be a trump card allowing holders to opt out of any generally applicable law.

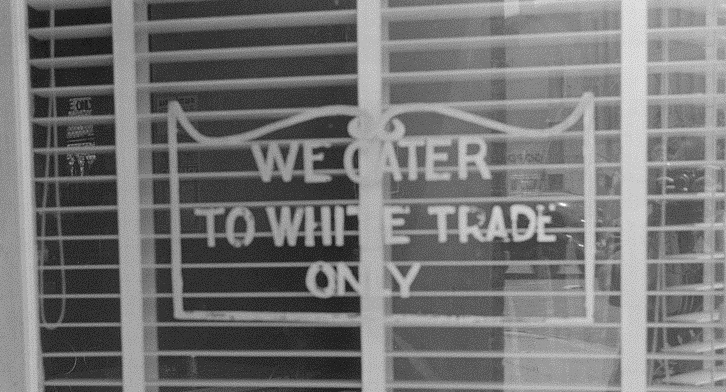

The problem, from their perspective, is that the historical parallel is too raw and too obvious: it wasn’t that long ago that many business owners also demanded the right to refuse service to black people (and, yes, claimed a religious justification for doing so). From both a legal and a cultural standpoint, this argument has already been settled: business owners who offer a public accommodation can’t pick and choose their customers on the basis of irrelevant characteristics such as race, gender, or sexuality.

The modern advocates of discrimination do their best to tiptoe around this parallel, but rarely with much success. Witness this exchange on Twitter, featuring the Heritage Foundation’s Ryan T. Anderson, who was raging about the aforementioned wedding-venue case:

.@ZackFord what you call "discrimination" is simply freedom. the basis of free association and contract and speech. Why do you hate freedom?

— Ryan T. Anderson (@RyanT_Anderson) August 21, 2014

That argument begged for what struck me as the obvious rejoinder: if “free association and contract” covers one kind of discrimination, shouldn’t it cover all kinds?

@RyanT_Anderson So you think the Civil Rights Act should also be repealed, I take it? Whites-only restaurants are OK with you?

— Adam Lee (@DaylightAtheism) August 21, 2014

That occasioned a sudden and sharp change of tone, as Anderson did a 180-degree turn to argue that “free association” somehow protects the right to discriminate against gay people, but not the right to discriminate against black people. See for yourself:

@DaylightAtheism The cases aren't the same. Look to the history: http://t.co/nR0CPi1qh5

— Ryan T. Anderson (@RyanT_Anderson) August 21, 2014

In this tweet, he linked to an essay also written by himself, in which he argues, basically, that only certain kinds of prejudice are old enough to qualify for legal protection.

Belief that marriage is a male–female union is shared by the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim traditions; by ancient Greek and Roman thinkers untouched by these religions; and by various Enlightenment philosophers. It is affirmed by canon, common, and civil law and by ancient Greek and Roman law… Only late in human history does one see political communities prohibiting intermarriage on the basis of race.

The first and most obvious point is that he’s drawing lines arbitrarily to arrive at his desired result. Bans on interracial marriage may be “late” compared to the entire span of human history, but as far as Western civilization goes, they’re very old indeed. In the United States, some of them date back to the 1660s, the colonial era. Why doesn’t this qualify as “old enough”? Why should it matter if a prejudiced belief is 300 years old or 3,000?

But more fundamentally, this argument is plainly irrelevant, since we’re not ruled by the dead hand of the past. The law in America isn’t based on what ancient Greek and Jewish philosophers believed; it’s based on the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And the Constitution requires equal protection of the law – which, as an overwhelming majority of recent court cases have agreed, means that arbitrary gender-based restrictions on the legal benefits of marriage can’t stand.

On the flip side of this, defining our laws solely by reference to what long-dead people believed would open the door to all kinds of evils that were ubiquitous in the ancient world: slavery, monarchy, theocracy, torture, genocide as a tactic of war. We reject these practices because we’ve made moral progress, because we recognize as injustice many things that were once widely accepted. Saying that some belief should be preserved just because it’s old is the clumsiest imaginable example of fallacious reasoning.

However, as faulty as Anderson’s argument is, he at least sees racial discrimination as a bad thing deserving of a legal remedy. There are conservatives and libertarians who take the opposite tack – who argue that we should repeal civil-rights and anti-discrimination laws, and bring back the days when lunch-counter owners could ban black customers or stores could hang out the “No Jews Need Apply” shingle. Senator Rand Paul said this in 2010, for example, though he later backpedaled on it; the same is apparently true of failed Senate candidate Todd Akin. Other, more marginal figures said so even less apologetically. Granted, this is still a fringe position – but the more legal losses that religious conservatives rack up in the battle over anti-discrimination laws, the more prominent I predict it will become.

Image: Sign on a whites-only restaurant in Lancaster, Ohio, August 1938. Original via Library of Congress.