(Author’s Note: The following reviews were solicited and are written in accordance with this site’s policy for such reviews.)

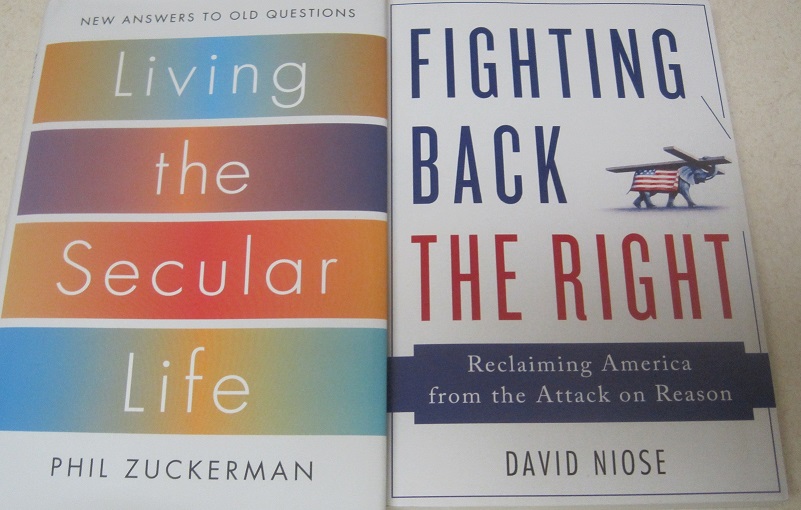

Fighting Back the Right by David Niose

I previously reviewed Nonbeliever Nation by David Niose, a past president of the American Humanist Association. His new book, Fighting Back the Right, tells the story of how the right wing became a formidable force in America’s culture wars and what we can do about it.

The modern conservative movement, in Niose’s account, is an alliance between wealthy corporate interests that want to end taxes and regulation, and grassroots religious right voters who want to grant favored status to Christianity. The aims of these groups overlap in significant ways: neither wants evidence-based policy that might, say, lead to restrictions on carbon emissions or mandate the teaching of evolution. And they’ve developed an alliance of convenience where the corporate right provides the funding, while the religious right provides the moral cover and the votes. Meanwhile, progressives are fragmented, fighting individual issues like church-state separation, LGBT rights, and science-based public policy without grasping how they fit together into a larger framework.

Niose recounts historical evidence to show how this nexus has developed over the last few decades. There are some excellent tidbits here, including some I didn’t know: for example, the first president to end a speech with “God bless America” was Richard Nixon, in 1973, the midst of Watergate. He argues that the accumulation of power by business interests was something the founders warned about: for example, James Madison called the indefinite ownership of property by corporations “an evil which ought to be guarded against”. But we’ve failed to heed this advice, allowing corporate rights and therefore corporate power to balloon out of control.

With all that said, I was expecting a specific, bullet-pointed action plan for secular and progressive Americans: how to organize people, how to craft our messaging, how to influence political candidates, what issues we should focus on first, and so on. Surprisingly, there isn’t anything like this. Instead, his only real suggestion is that our top priority should be to pass a constitutional amendment repealing corporate personhood, so that Congress can stem the flow of big money into politics, and that everything else will follow from there.

Whether you agree with this or not, as an action plan, it’s much too vague. First of all, how are we going to pass this amendment, given that we’d have to get it through the same political gauntlet where corporations wield enormous influence? Niose doesn’t say. He doesn’t even suggest exactly what he thinks the text of the amendment would be (and writing it is no simple task). And even if we passed it, what then? Without corporate dollars backing them, would the religious right just melt away? I doubt that. At best, that would be the only first step in a long process of splitting up the corporate oligarchy/social conservative alliance.

Living the Secular Life by Phil Zuckerman

I’ve often had occasion to cite the work of Phil Zuckerman, a sociology professor who’s made it his academic mission to study the influence of secularism and atheism on society. That’s I was very pleased to see he’s written a book, Living the Secular Life, that sums up his most important research.

Zuckerman’s main point is a simple one: that the correlation between religion and societal success is real, but it doesn’t point in the direction that religious apologists want it to. In fact, the world’s most secular societies are stable, peaceful, democratic and egalitarian, while many of the most religious countries are poverty-stricken, unstable, violent and autocratic. On virtually every metric of societal development – from the Global Peace Index to the Successful Societies Scale – the world’s less-religious countries come out ahead. Studies also find that secular people, on the whole, are less racist, less supportive of torture and corporal punishment, less in favor of military aggression, more likely to support civil tolerance and science… the list goes on and on.

This isn’t to say that the decline of religion necessarily causes these good outcomes – it’s possible and even likely that they have a common cause – but it does flat-out contradict the ubiquitous apologetic that the loss of religion will inevitably lead to social decay and anarchy. Much the contrary, it seems that societies become healthier as their people give up religion. And that’s very good news for secular Americans, since our numbers are rapidly growing. As Zuckerman says:

…the number of nonreligious Americans has increased by well over 200 percent over the last twenty-five years, making it the fastest-growing “religious” orientation in the country. [p.5]

The balance of the book is devoted to interviews with secular individuals whom Zuckerman has met in the course of his research. They speak on the topics that together make up a complete worldview: how our morality is based on conscience and reasoned reflection rather than obedience; how we raise children; how we find meaning in life; how we react to adversity and deal with death. One of the best, most gripping stories was from Zenon Neumark, an atheist Jew who survived the Nazi occupation of Poland.

This is one of the few books that I’d wholeheartedly recommend giving to a religious friend or relative who’s suspicious of atheism. It accomplishes the feat of making a case for secular life in a sympathetic, non-aggressive, yet compelling way. And for people who are arguing the benefits or detriments of atheism, there’s a wealth of well-supported statistical evidence to use as a resource.