Summary: Morbid, irreverent and funny, but a subtle and compassionate humanism runs throughout.

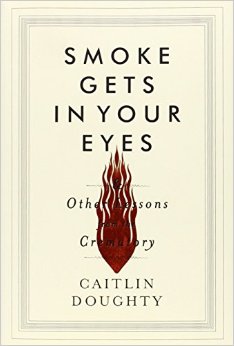

Caitlin Doughty is a mortician, the creator of a popular YouTube series answering questions about the funeral industry, and the founder of the Order of the Good Death, a “death acceptance” organization dedicated to helping people reconcile with mortality. Her book Smoke Gets in Your Eyes and Other Lessons from the Crematory grows out of that mission, offering a disarmingly honest glimpse into an industry that still strikes many people as deeply mysterious and forbidding.

The modern funeral industry is dedicated to making sure that the rest of us never have to confront death. In America today, most people die in hospitals and are immediately whisked away to the funeral home, ensuring that the majority of ordinary people never have to see, spend time with, or touch a dead body; whereas in most cultures throughout history, it was routine for people to die at home and for their families to wash, wrap and bury the corpse.

This historically unusual state of affairs came into being during the Civil War, when soldiers were killed on distant battlefields, making embalming a necessity so that their bodies could be shipped home by rail. This change heralded the professionalization of the funeral industry, where undertakers began to think of themselves as highly trained specialists just like doctors. Doughty’s argument is that the pendulum has swung too far, to the point where morticians think they’re the only ones capable of handling death, which couldn’t be further from the truth. Worse, it’s made death an alien and unfamiliar phenomenon in our culture, which creates needless anxiety and other unhealthy attitudes: such as the craze for quack anti-aging treatments, or futile, costly medical interventions that only delay death without increasing the quality of life. I was especially amused by her dig at transhumanism:

It is no surprise that the people trying so frantically to extend our lifespans are almost entirely rich, white men. Men who have lived lives of systematic privilege, and believe that privilege should extend indefinitely.

…Death might appear to destroy the meaning in our lives, but in fact it is the very source of our creativity. As Kafka said, “The meaning of life is that it ends.” Death is the engine that keeps us running, giving us the motivation to achieve, learn, love, and create. [p.229]

I previously read Jessica Mitford’s The American Way of Death, a stinging expose of how the funeral industry rakes in profits by exploiting the bereaved. Doughty isn’t nearly as polemical, although she does criticize lavish vaults and caskets, intricate embalming and other preparations that, in her view, serve only to isolate the living from the reality of death. In their place, she advocates alternatives like green burial, no-frills cremation, or even home burial, in places where the law permits it. She’s a firm advocate of the idea that we should take charge of our deaths again, and claims that this would go a long way toward alleviating our collective death anxiety.

As you might guess from the morbidly funny title, Smoke isn’t a book of gloom or woe. It argues that we should treat mortality with acceptance, as an inevitable part of existence and nothing to be feared or excessively lamented. There are poignant parts – one of the best chapters was about Doughty’s first trip to a hospital to collect stillborn babies for cremation – but there are just as many parts that are refreshingly irreverent, slightly profane, painfully honest, and even funny.

Despite Doughty’s reassuringly cheerful narrative presence, this book doesn’t shy away from facing death and all it entails. She frankly describes the reality of decomposition, the gruesome process of embalming, the dismembering of bodies for medical research. And there are some anecdotes from her time working in a crematory that are only for the strong-stomached (let’s just say that liquefied human fat plays a prominent role in one). But that’s very much the point: although we might think of ourselves as ethereal loci of pure thought, the reality is that we’re embodied creatures, squishy bags of meat prone to the same decay and dissolution as all other flesh, and we do ourselves no favors by shying away from this.

At the same time, she offers a hopeful, even encouraging message. Every culture, Doughty says, has “death values” – a body of tradition and ritual that develops around mortality. As our culture becomes increasingly secular, the traditional death values based in religion are crumbling. But that’s a good thing, she says, because it liberates us to reinvent our relationship to death as we see fit:

The fastest-growing religion in America is “no religion” – a group that comprises almost 20 percent of the population in the United States… At a time like this, there is no limit to our creativity in creating rituals relevant to our modern lives. The freedom is exciting, but it is also a burden. We cannot possibly live without a relationship to our mortality, and developing secular methods for addressing death will become more critical as each year passes. [p.215]

For all Doughty’s up-close-and-personal experience with death, she espouses what seems to be a staunchly secular and humanist viewpoint. In the conclusion, she offers a poetic, Lucretian musing on the eventual end of her own life and the substance of her body rejoining the endless cycles of nature: “I made the choice to die content, slipped into the nothingness, my atoms becoming the very fog that cloaked the trees”. For those who feel a need for them, she doesn’t pour scorn on the comforts of religion or tradition; but a life well-lived, and an honest reckoning with mortality, are the only things that truly immunize a person against fear of death.