In the wake of the protests and riots that convulsed Baltimore after the death of Freddie Gray, there was unexpected and welcome news: state’s attorney Marilyn Mosby moved quickly to indict the police officers who let him die in their custody. I was surprised and pleased to see that she threw the book at them, including by charging one with second-degree murder.

But even if the indictment sticks, even if the officers are convicted, there’s a deeper problem which hasn’t been touched. The tide may be turning against brutal policing, but the root of the problem is racism whose goal was to keep black communities poor, disenfranchised, and starved of opportunities for advancement. And the politicians and landowners responsible largely succeeded in that goal, in a way that’s readily visible even today, generations later, in supposedly post-racial America. The protests, riots and other disturbances we’ve seen are the result of decades of pent-up frustration boiling over – the language of the unheard, as Martin Luther King Jr. put it.

Americans like to think that our country is the land of opportunity, the nation of unlimited promise, where anyone who’s got a great idea or a lot of elbow grease can make something of themselves and get rich. But the reality has never lived up to that rosy aspiration. The truth is that our present distribution of wealth isn’t the product of chance, nor is it the result of hereditary differences in talent or work ethic. The gap between rich and poor, and especially white and black, is a deliberate creation of the elite. The ghettos were planned out, every bit as much as the suburbs, through a combination of racist law and private discrimination.

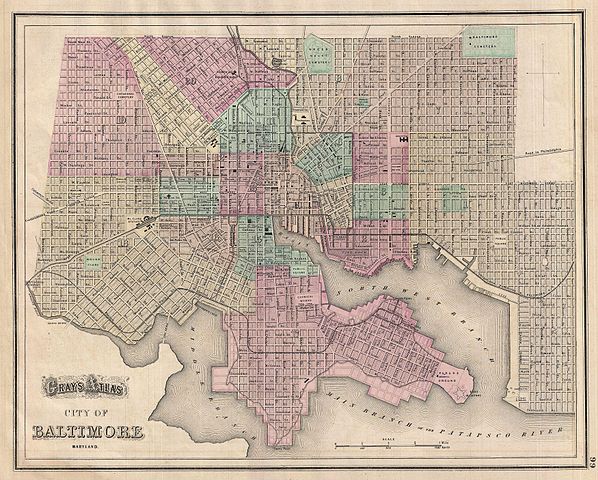

Baltimore, not coincidentally, is a prime example. In the early 20th century, racial segregation was an omnipresent system of control, enforced with the collusion of private parties and every level of government. Its Jim Crow laws, which were among the strictest in the nation, forbade black citizens from buying houses on majority-white blocks and vice versa. Building inspectors were the tools of enforcement, filing stacks of nuisance citations against landlords who wouldn’t cooperate. Banks also got into the act with redlining policies, which either outright denied mortgages to black borrowers or corraled them into specific neighborhoods. And the Federal Housing Administration, which could have been a powerful thumb on the scale defending civil rights, instead backed up Baltimore’s apartheid by refusing to guarantee loans in black communities.

Thus segregated, minority neighborhoods could be starved of amenities like good schools, accessible transportation, and job-creating investment. When black borrowers did get loans, they were often predatory “contract” loans where their homes could be repossessed if they missed a single payment. Again, Baltimore was one of the leaders, but policies like this were replicated in towns and cities all over the country.

Last but not least, when black families and communities defied the odds and started building wealth in spite of all the obstacles put in their path, white racists often incited riots on some flimsy pretext to destroy them. The Tulsa riot of 1921, where the wealthy black community of Greenwood (known as “the Black Wall Street”) was burned down and many of its citizens killed, is the chief example.

Even though restrictive covenants, redlining and other racist policies no longer have legal force, their effects are real and ongoing. Black families who were denied the opportunity to acquire wealth through homeownership can’t pass that wealth down to their children, propagating the racial fault lines of poverty down through generations. The effect is strikingly persistent: Baltimore’s mostly-black slums today map almost exactly to the segregated slums of the 1910s. As I’ve mentioned before, studies show that laissez-faire, rags-to-riches America has one of the lowest rates of social mobility among all developed nations, and this is a big part of the reason why.

I’ve written about drug prohibition and the prison-industrial complex, which was conceived of as a tool for mass oppression and disempowerment of black communities. This is another axis of that same oppression. But while prohibition could be ended and the prison-industrial complex dismantled with just a few pieces of legislation, it’s a lot harder to see how lingering residential segregation can be fixed.

Remarkably, one of the politicians who tried was George Romney (yes, Mitt Romney’s father). As President Nixon’s housing secretary, he tried to break up the ghettos with integration and affordable housing – but Nixon put a stop to it, and most politicians from both parties have refused to look the problem in the eye ever since. Another proposal is direct reparations, although who would be compensated and how much are formidably difficult questions.

Whatever the solution may be, this problem can’t be solved if the nation doesn’t see it or refuses to address it. If we wait for the latest wave of civil disturbance to die down and then surrender to collective amnesia, there’s every reason to believe we’ll end up right back here in another ten, twenty, a hundred years. De facto segregation has survived long enough on its own that there’s every reason to believe it will never end unless we take concrete steps to remedy it. If the new civil rights movement succeeds in getting America to at least acknowledge this painful history, that may at least be the first step.

Image: Baltimore street map, 1874. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.