My post last week asking LGBT people and allies why they still consider themselves Christian touched off a firestorm. Both in the comments here and on Twitter, I got a flood of responses from liberal Christians – some polite and friendly, others extraordinarily hostile and aggressive.

There were several objections that came up repeatedly. I want to gather these common objections so I can respond to them in one place:

There are LGBT-friendly and inclusive Christian churches. This was a point that many people brought up. And while I grant that these churches exist, the point few seemed willing to grant in return is that they’re very much in the minority. For instance, the famously tolerant United Church of Christ has just under 1 million members, which is less than one-third of one percent of the U.S. population. By comparison, the no-gays, no-women-pastors, no-apologies Southern Baptist Convention has over 15 million. Another person brought up Spiritus Christi, a pro-LGBT Catholic community in Rochester, New York… which was excommunicated by the Vatican in the 1990s, which rather proves my point. (Here’s another story about a gay priest being defrocked.)

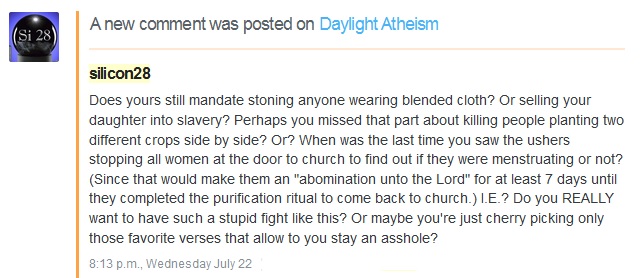

These liberal churches are honorable but rare exceptions – islands in a sea of prejudice – and I believe it’s fair to ask their members whether they want to remain part of a larger system that’s responsible for so much pain and suffering, even if they’ve personally found a place that accepts them. And even the tolerant churches still use the same Bible as the fundamentalists, with the same verses commanding death for gay people – a point I made that enraged one liberal Christian, who went off snarling insults and profanity at me as if that was my fault:

Another Christian went from “I’m an atheist ally” to “Non-Christians don’t care about the golden rule” in the space of about twelve hours.

There was also this comment from Katie Delia, who gave far and away the fairest and most thoughtful criticism I got:

In 2015, 59% of Americans support same-sex marriage. 83% identify as Christian. Even if every non-Christian is pro same-sex marriage, that means that 42 out of that 59% has to be Christian.

I’d respond that, while it’s true that a significant number of people who identify as Christian support marriage equality, it’s also true that many people who identify as Christian are merely nominal believers with few meaningful ties to the faith. More specifically, surveys consistently find that what best predicts support or opposition to gay rights isn’t religious affiliation per se, but frequency of church attendance.

What’s really happening, I would argue, is that people are becoming less Christian. They attend church less often, they’re less likely to consult or obey religious authorities, they’re more likely to make up their own minds without reference to religious teachings – and to the extent that they do that, they become more supportive of gay rights, even if they continue to call themselves Christian for cultural reasons.

I believe in Jesus, not the Christian church. This was the second most common argument I got – that LGBT Christians, though they may be oppressed, are still Christians who believe in God’s existence and Jesus’ divinity. It’s safe to assume I’m aware of that. Nevertheless, it’s a fact that many people have become atheists due to irreconcilable disagreement with a church that refused to recognize their humanity or engaged in overt injustice. I’ve read many testimonies from people who’ve followed just that path; I’ve witnessed it personally, in some cases.

Another way of phrasing the question is this: How can you reconcile belief in a morally good deity with the fact of pervasive, violent prejudice in the holy texts you believe in or the history of the church you belong to? How is this not a contradiction which suggests that either your belief or your church is mistaken at some deep level? And if they can be so badly mistaken about that, what else might they be mistaken about? Even if this realization doesn’t immediately make someone an atheist, it’s often the first in a chain of falling dominoes that can lead there. (Similar reasoning played a part in my own deconversion.)

If your moral reasoning is based only on faith, you have no way of knowing that your beliefs are correct rather than those of the anti-gay conservatives. I made this point on Twitter to a Christian named Jeff Chu, who puzzlingly conceded that while he personally believes in equal rights, he might be wrong and the homophobes might understand God’s will better than him. When I described his position this way, he got upset and said I was “willfully misunderstanding” him – but judge for yourself.

It’s impossible for me to change my beliefs. One instance of this argument came from Jeff Chu again, who said, “I can’t just choose not to believe in God — just as an atheist can’t just choose to believe”. Another commenter spoke of their beliefs as “hard-wired” and said it would be “impossible” for them not to believe.

While it’s true that people can’t alter deeply held beliefs at will, people’s beliefs do change. There are countless ex-believers who can testify to that. And often, the first step of deconversion is realizing that there are alternatives – that it’s possible to leave and seek new and better communities beyond the one you’re currently in. I wrote this post with the hope that it could supply that necessary imagination-stretching for someone.

It’s wrong to question or criticize other people’s choices. This was possibly the oddest response I got. For example, Dianna Anderson hauled out the old trope that atheists are just like evangelical Christians because we both want to change people’s minds, which is arrogant and disrespectful of us. She also claimed that I was saying “[her] faith makes [her] less of a feminist or a moral person” – something I explicitly disavowed in my original post. Another correspondent on Twitter said that it was unfair that any LGBT Christian “had to” defend their religious beliefs to me when they already get enough criticism from their own church.

To reiterate the obvious, no one has to defend or justify themselves to me. Some people chose to, and I’m happy to engage with them. But I don’t accept the notion that other people’s choices are beyond question or critique. Still less do I accept that it violates someone’s rights even to ask them to explain the choices they made. I don’t reject out of hand the idea that someone could change my mind; if there’s an argument that could convince me something I believed was wrong, I want to know about it. I hold other people to the same standard, assuming that they’re adults who can evaluate evidence and logic and come to their own conclusions. I don’t hold that religious beliefs or any beliefs ought to be sheltered from contrary opinion.

Atheists aren’t perfect either! I made this point myself in my original post, knowing that it would inevitably come up, but that didn’t stop people from throwing it at me as if it was something I had never thought of before. For instance, Eliel Cruz:

.@DaylightAtheism and you operate in this fantasy world that atheists will just accept all of my identities and do not hold any prejudices.

— ELIEL CRUZ (@elielcruz) July 21, 2015

Or Dianna Anderson again, with the argument of “who’s to say whether atheists or Christians are more tolerant?”

Who’s to say atheism is more accepting? The problems of exclusion are not unique to Christianity. @DaylightAtheism @elielcruz

— Dianna E Anderson (@diannaeanderson) July 21, 2015

Once again, for the context-allergic: I acknowledge that atheists have prejudices of our own. That’s not just unsurprising, it’s inevitable in any large group of humans. I’m well aware of the need to do better; it’s something I’ve written about many, many, many times. But on the specific question of whether LGBT people are more likely to be welcomed in the secular community than they are in the Christian church, the facts are undeniable. The non-religious are far more tolerant and supportive as a whole. This doesn’t mean that no one will ever experience prejudice, but to pretend that this data tells us nothing about the likelihood of that is dishonest.

To be perfectly honest, I was taken aback by the open hostility in some of the responses I received. It may be uncharitable, but I think that some – not all, but some – of the religious liberals who attacked me want to hear that they’re special snowflakes. They expect to be praised for their comparatively enlightened and cosmopolitan beliefs, and they were astonished and outraged to find out that I don’t exempt them from the criticisms I lob at the fundamentalists. Sorry to disappoint them, but that’s what “atheist” means! Faith is not and will never be a good way of making decisions, even if they’re decisions I happen to agree with.

I also think a lot of the anger aimed at me comes from cognitive dissonance. I’m sure that most liberal theists, especially LGBT people, are well aware of the tension between wanting to be tolerant or accepted and being part of a faith that holds a very different attitude. The stress of believing those incompatible ideas easily transmutes into rage at anyone who points out the unresolved contradiction. My post was calling to their attention something they prefer not to think about, and it doesn’t surprise me that many of them became defensive and hostile in response.