Content note: Contains some spoilers.

It says something about our era that so many of the most popular movies and TV shows are grim, depressing stories of disaster and dystopia. Is it a reflection of the popular mood? A sign that we’ve lost hope in ourselves and our ability to achieve great things? Why are there so few works of culture which make us feel optimistic, which tell us that better days are ahead?

This weekend, I saw a movie that’s a welcome exception to that gloomy trend: Ridley Scott’s The Martian, based on the novel by Andy Weir. It’s the rare disaster-spectacle story that doesn’t argue for humanity’s powerlessness against nature. If anything, its message is the opposite.

When the movie opens, a crew of astronauts (seemingly all American) is already on Mars, carrying out a scientific survey mission. Their plan is to live on the red planet for two months while they collect samples to return to Earth. But when a gigantic, dangerous sandstorm strikes, they’re forced to abort the mission and blast off early. As they scramble back to their rocket, one astronaut, Mark Watney (played by Matt Damon) is hit by flying debris that knocks him unconscious and damages the suit monitor that tracks his vital signs. Believing him dead, the rest of the crew blasts off without him.

Watney wakes up to find himself alone on Mars, stranded with no way to communicate, and with only a few weeks’ worth of food. But he refuses to give in to despair. Instead, he buckles down to figuring out how he can stay alive until NASA discovers his plight and sends a rescue mission, which even in the best case could take several years.

Survival in the airless, lifeless, subzero desert of Mars poses one seemingly insurmountable challenge after another: how to grow his own food, how to travel across the planet’s surface, how to communicate with Earth, how to fend off loneliness and depression. Watney tackles each one with slow, methodical resourcefulness and deadpan humor. (He keeps a video diary, which is a welcome glimpse into his inner monologue and keeps the Martian scenes lively.) In one destined-to-be-quotable line, he declares, “I’m gonna have to science the shit out of this.” At the same time, NASA mission control discovers that Watney is alive, and a subplot centers on their frantic efforts to find a way to rescue him.

The Martian is, as it should be, a powerful argument for the scientific method and the calmly rational outlook it engenders. Watney electrolyzes hydrazine to make hydrogen and burns it with oxygen to make water. He empties the habitat’s latrines and mixes the sludge with Martian regolith to create soil that he can grow potatoes in. He digs up the RTG used to power the habitat module so that the heat of decaying plutonium will keep him warm. In his most spectacular feat, he travels to the final resting place of the Mars Pathfinder so he can scavenge its high-gain antenna to communicate with Earth. He faces setbacks and crises – an injury that requires gruesome self-surgery; a catastrophic airlock failure that destroys his precious crops; a NASA emergency resupply rocket that spins out of control and explodes after launch, denying him a cargo of food he was counting on – but while he has moments of frustration and rage, he always keeps a cool head when it’s needed the most.

In the final act, a NASA engineer comes up with a daring plan: the spacecraft carrying the rest of the mission crew to Earth can perform a gravitational slingshot around our planet and head back to Mars instead. It’s an all-or-nothing gamble that could be the only way to rescue their fellow crewman, but it could also seal the doom of the entire crew. You can probably guess what they choose and how it turns out, but seeing them overcome each obstacle along the way gives the movie its thrill.

For the most part, The Martian is as hard as sci-fi gets, and the problems Watney faces and the ways he solves them are well-grounded in plausibility. There are a few exceptions. The hurricane-like dust storm that forces the crew to abort the mission and sets up the main plot is the biggest: in reality, Mars’ atmosphere is too thin to sustain dangerous winds. The movie also didn’t dwell on the health effects of long-term exposure to cosmic radiation, especially given the extended voyage that the crew endures.

But these are quibbles. The movie’s deeper message is fiercely optimistic: a vote of confidence in the power of human ingenuity bolstered by science, the indomitable will to survive in the face of overwhelming odds, and not least, the good will and heroism of a world which doesn’t think twice about launching an international and interplanetary rescue mission for the sake of a single life. (While the main character is a white man, the movie is well-served by a diverse and realistic supporting cast that includes women and people of color in almost every prominent role.) I won’t deny I got choked up at a few points.

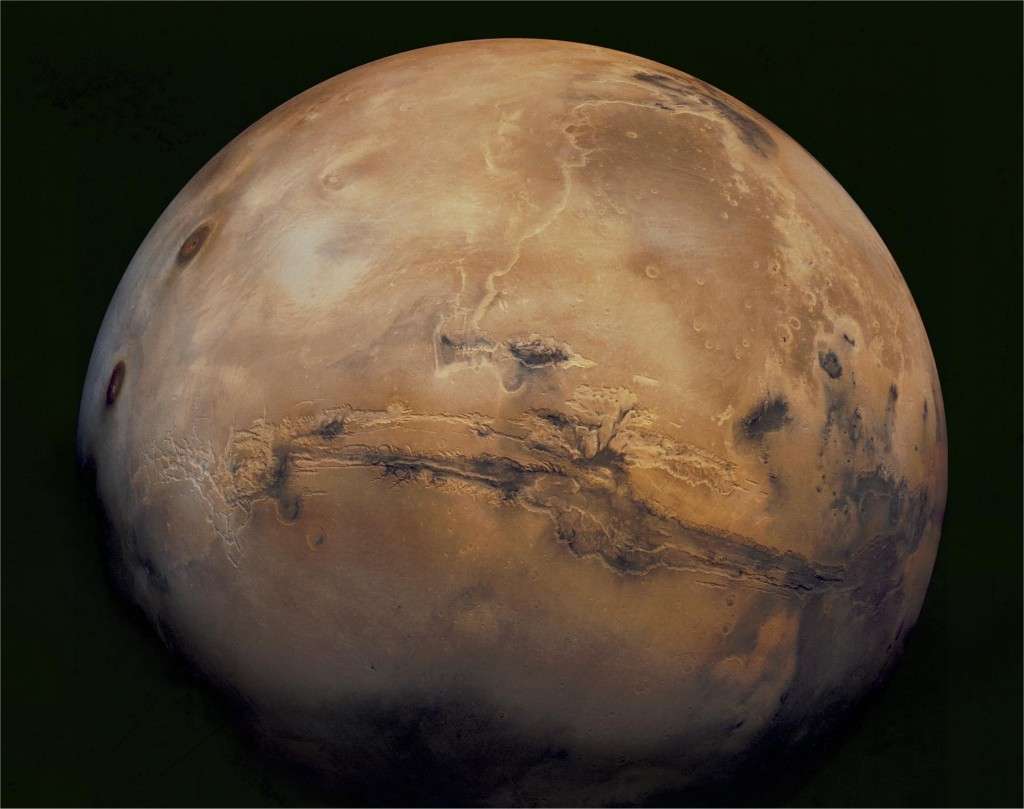

Most of all, it’s a clarion reminder of why we should be out there. Mars is a formidable foe, but never hostile or malicious. In fact, the movie goes out of its way to show the vast and beautiful desolation of the Martian landscape, a red-orange wilderness of rugged ridges, ancient craters and sweeping valleys. At his lowest point, Damon’s character declares that he’s not afraid to die if it’s in the service of a cause as big and important as this one. The Martian never suggests that the cosmos wasn’t meant for us. On the contrary, it’s a stirring argument that, despite the inevitable setbacks, we have it within us to overcome every challenge that awaits.

Image: Mars from Viking 1, via NASA/JPL-Caltech