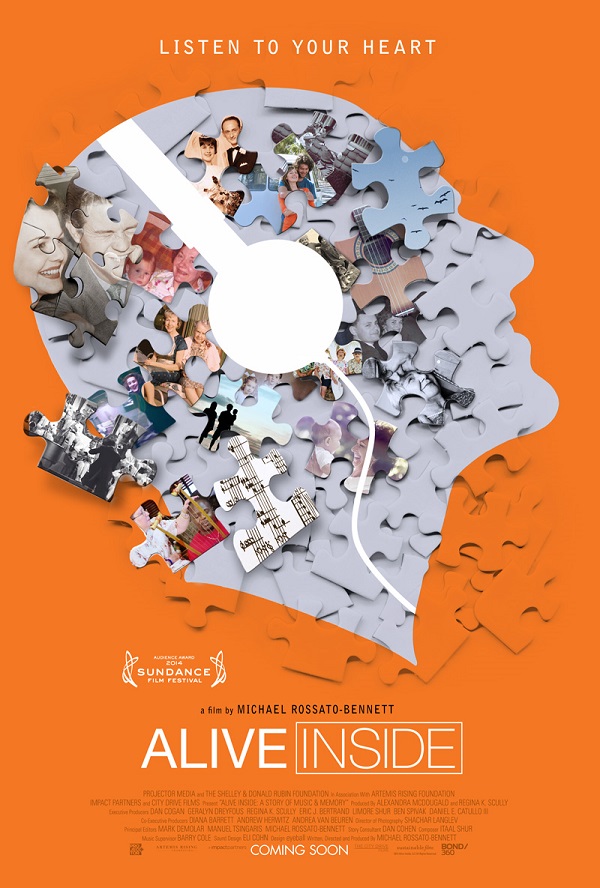

Alive Inside is an award-winning documentary by Michael Rossato-Bennett about the work of Dan Cohen, a social worker from Long Island, and the charity he founded, Music & Memory. (Disclaimer: I know Dan personally, and I’ve contributed to his charity.) It spotlights a slow-rolling demographic crisis poised to overtake the Western world, and offers at least one startlingly powerful idea that could be part of the solution.

In the next few decades, the developed world is going to confront something unprecedented in human history: an inverting demographic pyramid. As people live longer and have fewer babies, an increasing share of the population is made up of the elderly. This has the potential to cause all kinds of economic strains – shrinking cities, ballooning pension costs – and, not least, poses the question of how to pay for the care of people with dementia. This is a major burden already, and it’s only going to get bigger: the U.S. already has about 4.7 million people living with Alzheimer’s disease, and that number is set to triple by 2050.

So far, our best solution is to warehouse elderly dementia sufferers in sterile, hospital-like nursing homes where they’re fed, bathed and medicated but little else. As anyone who’s visited one can attest, even the best of these are unenviable places to live, and the worst are houses of horrors. Deprived of stimulation and meaningful social interaction, it’s no surprise that most of the patients either retreat into catatonia or erupt in psychosis, and they’re often heavily drugged to make them compliant.

To be fair, caring for dementia sufferers is an enormously taxing job, whether for the underpaid and overworked carers who staff these nursing homes, or for family members who rarely have the time, or the money, or the training to do it themselves. But it’s impossible to believe that there can’t be a better way.

Alive Inside suggests one, based on an astonishingly simple discovery: when used as therapy, music rekindles the brain at a very deep level. When elderly dementia patients listen to the music of their youth – songs from the era they grew up in, the music they loved and that defined their lives – they wake up. Where they were slumped and comatose, they become chatty and vivacious: talking, singing, tapping their feet, dancing in place. Memories buried for decades resurface, and you can see the person emerge, shaking off the slow snowfall of years and infirmity. I wouldn’t normally use this word, but the result can be nothing short of miraculous.

One of the most famous clips from the documentary is of a 92-year-old man named Henry Dryer. If you can watch this and not cry, you must have a heart of stone:

Dan Cohen’s charity, Music & Memory, has as its mission to make more moments like this possible. But it faces bureaucratic inertia and other obstacles. Among its other subjects, the film interviews the doctor who invented Aricept, the world’s best-selling anti-Alzheimer’s drug, who freely admits that it’s not as effective as music therapy can be. Yet he and all the other professionals in our health-care system are constrained by perverse incentives. Doctors can dash off countless prescriptions for psychoactive drugs – most of which do little more than make patients easier to deal with by sedating them into a stupor – and insurance companies and the government will freely pick up the tab, which means all of us bear those costs somewhere down the line. But a refurbished iPod costing less than a single day’s medication isn’t covered, because it isn’t “medicine”.

The film doesn’t delve too deeply into the neurological basis for how music therapy works, although it does include an interview with Dr. Oliver Sacks, in what must have been one of the last projects he participated in before his death in 2015. I thought more science would have been welcome, especially more statistics on how often this treatment works and how lasting the effects are. But for the filmmakers, that was largely beside the point.

More fundamentally, it asks us to reflect on what value we place on the elderly. Do we want to learn from their wisdom, from their accumulated life experience, and to make it possible for them to contribute in all the ways they can? Or do we treat them as an inconvenience, a burden to be shuffled out of sight just because they can’t work as hard or produce as much as the young?

It’s not hard to notice the underlying moral here. Regardless of the economics, the film hints that the real reason we’ve constructed this dehumanizing system of holding pens is because we, ourselves, dread losing our own mental and physical vigor one day, and we seek to push the unfortunate ones out of sight so as not to be reminded of what awaits us all. If that’s the fear that animates us, Alive Inside makes a powerful and moving case that growing old needn’t be a fate to be feared, and that even the ravages of age and dementia can’t deprive us of our essential humanity.

Image credit: aliveinside.us