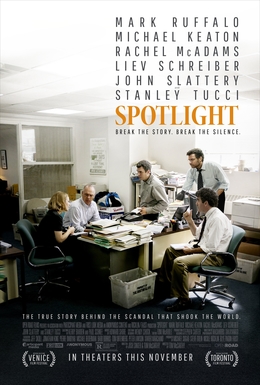

Spotlight tells the true story of four journalists at the Boston Globe who broke the story of how the Catholic church protected priests who molested children. Their reporting proved the complicity of Cardinal Bernard Law, the archbishop of Boston who’d been quietly shuffling pedophile clergy from one parish to another for decades, and led to an explosion of copycat reporting as cities and towns throughout the country and the world realized the same evils were happening in their midst.

Stories of sex predators in the ranks of the clergy have become so routine (on this site, as well as many others) that it’s easy to forget just how controversial and how explosive the idea initially was. For decades, when its power in society was unquestioned, the church acted virtually with carte blanche, and its victims suffered in isolation and silence. The Globe’s fearless 2002 exposé of child molestation in Boston, presented with proof that the hierarchy had participated in covering it up, won a Pulitzer Prize and was one of the first cracks that brought this dam of silence tumbling down. For that alone, we owe them a debt of gratitude.

Despite its subject matter, Spotlight resolutely refuses to be sensationalist. It sticks closely to the real history of events, resisting the urge to overplay or dramatize. There are courtroom scenes where they fight to unseal classified files, but they’re low-key conferences with the judge, not Hollywood-style confrontations with shouting and histrionics. The Globe reporters are warned many times about taking on the church, which is immensely powerful in Boston. But all that comes of it is that they get some doors slammed in their faces. There are no bricks hurled through their windows, no threatening late-night phone calls. It’s a movie as bloodless as black-and-white newsprint.

In the same way, while Cardinal Law is the villain of the story and the focus of all their reporting, he’s barely on the screen at all. There’s one short scene near the beginning where the Globe’s new editor, Marty Baron (Liev Schreiber), meets with an outwardly friendly Law who welcomes him to the city. There’s also a bookend scene near the end, where they call up the church before going to print to give them an opportunity to respond, and all they’re told is that Law declines to comment. In one sense, this is effective at depicting the evil as the product of a stolid and impersonal bureaucracy, rather than a handful of rogue church officials. Still, I wish the filmmakers would have put more of a human face on the men who did this, to show their reaction to the knowledge of their exposure. Nor do we see the impact of their story, except by implication. (Law, who should be in prison, instead left the country and was rewarded with a cushy retirement at the Vatican.)

But the movie’s understatedness gives all the more weight to its quiet voice of moral condemnation. While nothing is shown on screen, not even in flashback, we do see the reporters interview survivors of molestation who speak graphically about the suffering they’ve endured and the scars it left on their lives. It’s noted more than once that many of the victims ended up committing suicide. There’s a scene where one of the journalists, Sasha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams), confronts a retired priest who speaks with startling candor about what he did. Another reporter, Matt Carroll (Brian d’Arcy James), realizes that a house where the church sends pedophile priests for “rehabilitation” is on his street. A third, Walter Robinson (Michael Keaton), went to school where one of the predators taught, and wonders if it was just luck of the draw that he escaped unscathed.

And it’s good storytelling how we viewers witness the reporters’ slowly dawning realization of the scale of the conspiracy. At first, they believe they’re dealing with just one bad-apple priest, John Geoghan. They initially consider the story so minor, they almost pass up the chance to investigate it. But the deeper they dig, the more evidence of other predators they find, and the more apparent it becomes how systematically the church covered it up. In one scene, they speak with Richard Sipe, a former priest turned psychotherapist, who’s studied the problem and estimates that a city the size of Boston should have about ninety pedophile priests – a number that strikes them as ludicrously high. But when they comb through church directories to compile the names of priests who were moved from one parish to another unusually often, or who were mysteriously pulled off duty citing “sick leave” or some other euphemism, they find… 87.

Although the movie doesn’t lean too heavily on it, there’s a crisis-of-faith angle as well. All the Globe reporters are from Boston or have some other connection to the Catholic church, and we see their growing anger and disillusionment as they dig deeper. Near the end, they note that the scandal was hiding in plain sight all along and that they could have put the pieces together much sooner.

Last but not least, this movie testifies to the vital importance of investigative journalism. The Catholic church almost got away with it – they would have gotten away with it, if not for the Globe’s Spotlight team – and I wonder if a story like this could have been written today, with newspapers in free fall and the internet cannibalizing traditional media. Could the new-media sites that focus on viral content and clickbait have uncovered it? Would they have had the time, the persistence or the shoe leather? I fear the answer is no. And if investigative journalism is a dying art, what else might still be lurking in the shadows, waiting to be brought to light?