I recently became aware of the Long Now Foundation, a futurist group whose mission is to plant the seeds of long-term thinking in society. It’s a cause I have a lot of sympathy for, so it’s worth publicizing what they do.

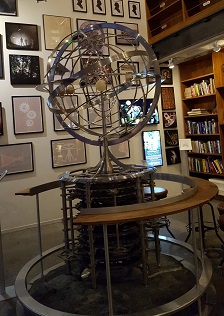

The foundation is headquartered at The Interval, a cafe and public forum in San Francisco’s Fort Mason. On display there is their library, a scale model of their 10,000-year clock (more on that in a moment), and all kinds of other curiosities. A screen above the bar shows a constantly changing kaleidoscopic display, powered by an algorithm that never repeats a pattern.

The Long Now Foundation runs a multitude of projects, like partnering with groups that want to resurrect extinct species, or creating the Rosetta Disk, an archive of information on over 1,500 human languages on a four-inch disk engraved down to microscopic levels, or managing the Long Bets project where philanthropists and philosophers wager about the future direction of society.

However, none of these compare to their grandest ambition: to build a clock that will run for 10,000 years without human intervention. Like the Onkalo repository from Into Eternity, it’s designed to outlast other artifacts of our civilization. The foundation has already selected land on mountains in west Texas and Nevada, both in high, dry desert wildernesses where weather and temperature swings won’t be a problem. (Appropriately, this climate is also congenial to bristlecone pines, which grow at the Nevada site.)

The Long Now clock will have all mechanical parts: no fragile electronics, nothing that would rust or corrode, no valuable materials that would tempt thieves, sufficiently simple to be repaired even with Bronze Age technology. It will be powered by diurnal temperature differences, and show, in addition to the time and date in our calendar system, the relative positions of the stars, the planets, the Sun and the Moon. Once per day, a series of chimes will play a unique melody that never repeats over the course of ten thousand years.

To see the clock, visitors will have to travel to the site, like pilgrims seeking out a monastic abbey; climb the mountain and enter through an airlock-like access hatch; scale a staircase winding up through a dark tunnel, past the clock’s massive gears and counterweights; and end up inside a human-made cavern, illuminated by a sapphire-glass cupola opening to the sky, where the great face of the clock beckons. The clock itself will keep time in splendid isolation whether anyone’s looking at it or not, but to see what time it currently is, visitors will have to wind up a secondary mechanism that syncs a display.

To be clear, none of this actually exists yet. The project is still in its beginning stages. (That said, Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, is one of their financial backers, so they have the resources.) There’s no set completion date, and the website chronicling the construction progress hasn’t been updated since 2011, but clearly the planners are prepared to take the long view.

The obvious question is, why bother with all this? What’s the motivation for this grandly pointless endeavor to build a huge, expensive, elaborate clock that almost no one will ever see over its long lifetime?

The foundation’s answer, which I think is a good one, is “to get people to ask that question”. In other words, the mere existence of the clock encourages everyone who hears about it to step into a long-term perspective. And that, in turn, invites us to contemplate the sustainability and endurance of our civilization.

Thinking about deep time encourages us to focus on what’s truly important, and not to fixate on fleeting headlines, trends or fashions that will disappear without a ripple in the grand scheme of things. It nudges us to ask whether we’re making the right decisions for humanity to survive and flourish in the long run. Without that counterweight, it’s all too easy to get caught up in short-term thinking and to make short-sighted decisions that impoverish the future. If you spend all your time looking down at your feet and none looking ahead at the horizon, you might end up walking right off a cliff.

To combat this all-too-human tendency, we need at least a few grand endeavors to remind us to lift our collective gaze every once in a while. As extravagantly, magnificently useless as the Long Now clock is, it and other projects like it could provide a subtle nudge on our decision-making so that there will be humans in ten thousand years to watch it tick to its conclusion. If that happens, the construction costs will be money well spent.