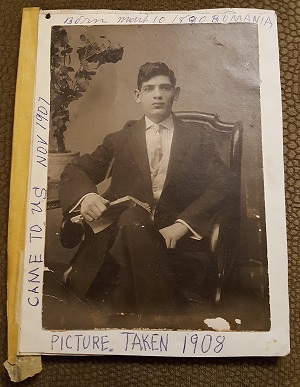

I was at a family gathering last weekend, and after dinner, we were looking through some old photo albums that had been discovered in the attic of my grandparents’ house. My attention was grabbed by this one, a picture of my great-grandfather Hymie, which is in excellent condition considering it’s over a hundred years old:

Born May 10 1890 Romania

Came to US Nov 1907

Picture taken 1908

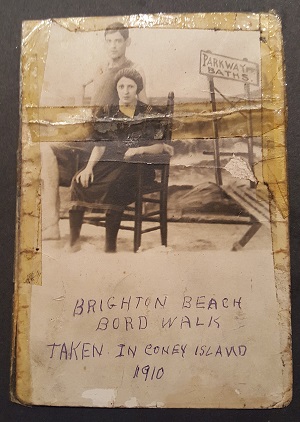

This one is a little more faded, but here he is together with my great-grandmother Rose:

Brighton Beach

Bord Walk

Taken in Coney Island 1910

It’s a strange thought, that these portraits in faded sepia are my ancestors. It makes it slightly easier to believe that I’m told I look strikingly like both of them (not quite an identical grandson, but close).

But appearances are the least part of what we inherit. As much as we might like to believe that we’re all self-made prime movers, the truth is that each of us comes into this world with a nature that we don’t choose. The evidence from twin studies and other research suggests that a broad and subtle lace of personality traits springs from our genes: altruism, risk-taking, even political beliefs and religiosity.

Of course, this doesn’t imply any kind of crude determinism. It’s more accurate to say that genes provide the base setting of our personalities. If a whole person can be imagined as a vast array of knobs and dials, each representing a given trait, then the genes set their positions at birth. Environment and upbringing then go to work, turning some knobs down and dialing others up, promoting some traits and discouraging others. Because of the staggering complexity of environmental influences, any simple-minded attempt to extrapolate a personality or a life outcome from a set of genetic markers is doomed to failure.

Still, the genes are the raw material. They contain the potential of all the different people each of us might have turned out to be, just as the shape of a rough block of marble determines what kind of finished sculpture it can become. That’s why it matters that some part of me comes from these people. Some part of that message that tells itself over and over through the generations originates with them.

The more I know about where I came from, the more I understand myself. I can make an educated guess about which strengths and virtues I’m most likely to possess, so I’ll know what I might excel at. I can also guess which temptations I’m most likely to fall into, so I can arrange my life to steer clear of them.

I don’t have a big extended family, so this is something I never gave much thought to while I was growing up. But it’s come into sharper focus now that I have a son. Every time I look into his eyes, I wonder what it means that half of him comes from me. I wonder what that means for his intelligence, his temperament, and where he’ll go and what he’ll do with his life. Naturally, I hope that I’ve given him a set of gifts that will help him, not an anchor weighing him down!

The other lesson I take from these pictures is a reminder to step outside the current moment occasionally. It’s easy – now more than ever – to feel that we’re at an unprecedentedly grim point in history, that our problems are uniquely insurmountable. But there’s never been a time when people didn’t feel the same way, didn’t worry about the same things. My great-grandfather’s life, and the lives of all the people who lived when these pictures were taken, mattered just as much to them. Their challenges, their struggles, their great social controversies were every bit as real and present to them as ours are to us.

But in spite of everything, they endured, they survived, and they kept building. They left us a world that was better – perhaps only in small, subtle ways – than the one they inherited from their ancestors. Just the same way, there will come a time when our generation is ancient history, and our descendants will know us only as faded pictures. Will we let them think that we gave up on them? Or will they remember that we soldiered on?