For all the madness and cruelty on earth, we’re privileged to live in a time when scientists are confirming that the skies are overflowing with planets friendly to life. And another big discovery that expands our cosmic horizon has just been announced:

NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope has revealed the first known system of seven Earth-size planets around a single star. Three of these planets are firmly located in the habitable zone, the area around the parent star where a rocky planet is most likely to have liquid water.

The discovery sets a new record for greatest number of habitable-zone planets found around a single star outside our solar system. All of these seven planets could have liquid water – key to life as we know it – under the right atmospheric conditions, but the chances are highest with the three in the habitable zone.

The initial discovery of this system was made by the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope observatory, known as TRAPPIST, in May 2016. The first report was that the system had three planets, but more detailed observations by NASA’s Spitzer and Hubble telescopes increased that number to seven. Even better, all seven appear to be rocky and Earth-sized, and at least three are in the habitable zone where oceans of liquid water could exist on the surface. (Given that the head of the TRAPPIST survey, Michael Gillon, is from Belgium, I suspect the name is a tasteful pun by some beer-loving astronomer.)

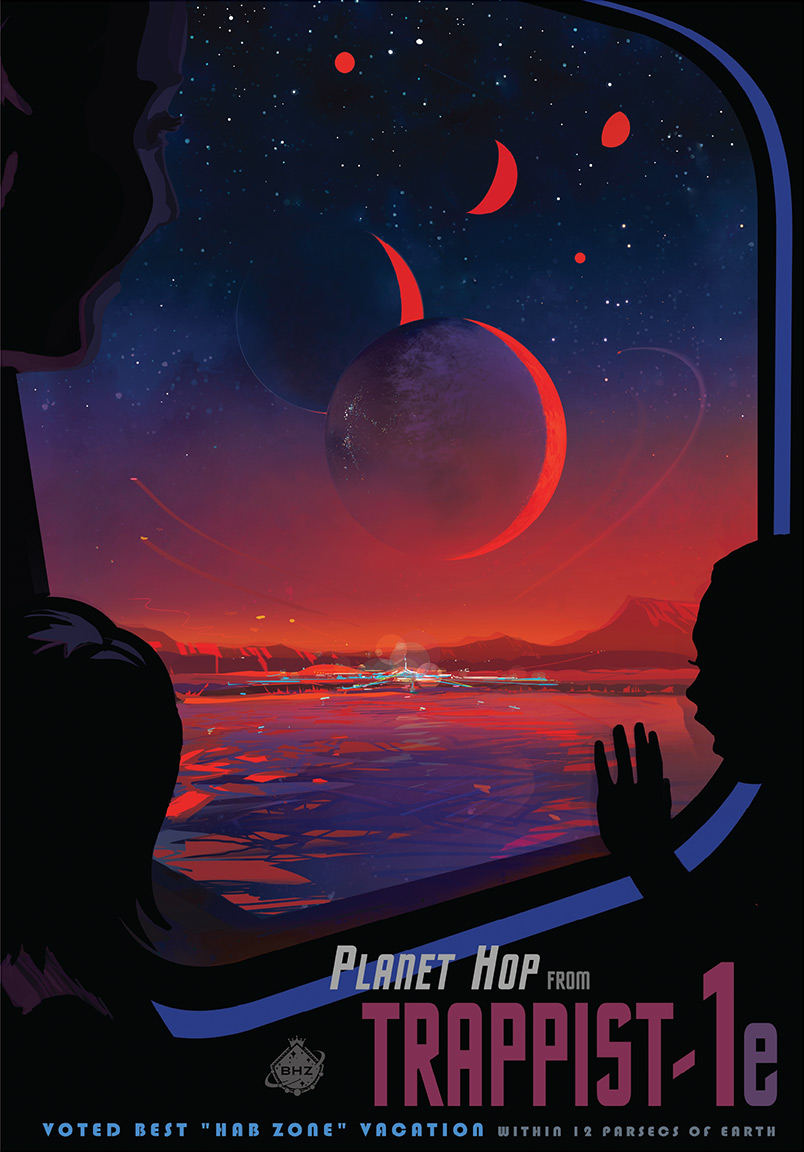

In many ways, the Trappist-1 system is similar to Proxima b, the nearby world on our doorstep I wrote about last year. All seven planets are closer to their sun than Mercury is to ours, but since their sun is a cool red dwarf, that makes them just warm enough, rather than fiery cauldrons. Also like Proxima b, they’re probably tidally locked to their home star, with one side in permanent day and the other in endless night. If a human was standing on the surface of one of them, here’s what they might see:

For a person standing on one of the planets, it would be a dim environment, with perhaps only about one two-hundredth the light that we see from the sun on Earth, Dr. Triaud said. (That would still be brighter than the moon at night.) The star would be far bigger. On Trappist-1f, the fifth planet, the star would be three times as wide as the sun seen from Earth.

As for the color of the star, “we had a debate about that,” Dr. Triaud said.

Some of the scientists expected a deep red, but with most of the star’s light emitted at infrared wavelengths and out of view of human eyes, perhaps a person would “see something more salmon-y,” Dr. Triaud said.

Best of all, the Trappist-1 system is just 40 light-years away – an immense distance in human terms, but a very short step on a cosmic scale. If we were to imagine a human or posthuman colonization wave spreading out from Earth into the galaxy, this might well be the next hop out from Proxima b. With seven planets to choose from, this could be a major port of call for interstellar voyagers.

This new discovery provides further evidence in support of the theory that planets are abundant around red dwarf stars, the most common stellar type in the Milky Way. That means tens of billions of potential worlds, all waiting to be discovered.

With so many rolls of the cosmic dice, it seems more likely than ever that at least one could harbor life. Even if we won’t be visiting any of these planets any time soon, the next generation of space-based telescopes may be able to observe them directly. A spectroscopic study of their atmospheres – or, more implausibly, the detection of a radio signal – could be the crucial clue that reveals the presence of life and proves once and for all that we’re not alone in the universe.

Image credit: NASA-JPL/Caltech. Don’t miss the other posters from the Exoplanet Travel Bureau.