If we ever overcome our differences and make it into space, there’s a universe of wonders waiting for us. This month, NASA unveiled another of those wonders with the announcement of hydrothermal vents on Enceladus.

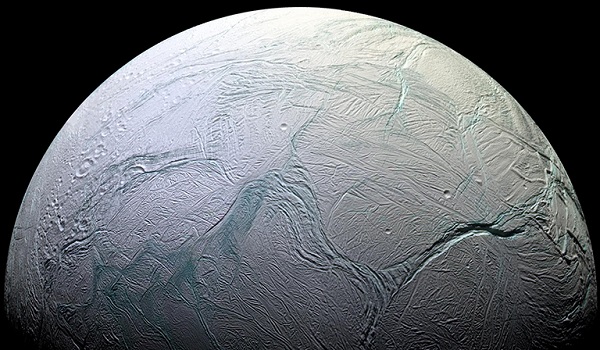

Enceladus is one of Saturn’s moons. Although it’s tiny, barely 300 miles in diameter, it has a long history of tantalizing skywatchers. It’s the most reflective body in the solar system because it’s entirely covered in ice. The Voyager 2 flyby found a smooth and geologically young surface, with relatively few impact craters but a wide variety of canyons, grooves and ridges dubbed “tiger stripes“. All these features hinted that Enceladus isn’t a dead, frozen iceball, but a living world with tectonic activity churning and reshaping its surface.

Further revelations had to wait for NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which in 2005 detected geysers blasting plumes of water, gases and simple organic compounds into space from Enceladus’ south polar region. Further research showed that the plumes also contain grains of silica that must have formed in hot, alkaline water, 190 degrees F or more.

Although this proved that there was liquid water under the ice, we couldn’t be sure how much of it there was. Enceladus’ geysers could be from a small local sea, or a pocket of water within the ice that was melted by tidal heating. But the true answer turned out to be more exciting. Detailed measurements of Enceladus’ orbit show it has a slight wobble that can’t be accounted for if the entire body is solid. There must be a liquid layer – in other words, a global ocean beneath the ice.

With this discovery, Enceladus joined Earth, Jupiter’s moons Europa and (possibly) Ganymede in the exclusive club of solar system worlds with water oceans. That alone would make it an object of great interest. But the latest discovery opens up an even bigger possibility.

A new analysis of Enceladus’ plumes reveals that they also contain molecular hydrogen. Given that Enceladus is too small for its gravity to hold onto primordial hydrogen, this is almost certainly created by chemical reactions between water and hot rock. That’s the same process that creates alkaline hydrothermal vents like Lost City on Earth. And on Earth, those vents give rise to thriving ecosystems that survive without sunlight, powered by microorganisms that consume hydrogen and give off methane.

With this discovery, we now know that Enceladus has all the ingredients for life as we know it: liquid water, simple organic compounds, a source of heat and energy. As this article points out, it’s been proposed that seafloor vents are where life began on Earth – the iron-sulfur world hypothesis. It’s natural to wonder whether Enceladus’ vents might have given rise to life in the same way.

It’ll be a long time before we’re able to send a submarine into the Enceladan ocean to confirm or refute this hypothesis. But between this, the oceans of Europa, the organic compounds raining down on Titan, the hints of strange chemistry on Mars and Venus… it’s unlikely, but by no means impossible, that the solar system is verdant with life. When we finally venture out among its worlds, if we find life in abundance everywhere it can exist, that will tell us something important. And if we don’t find life, even in places where it could exist, that too will tell us something significant about the universe and our place in it.

Image credit: NASA/JPL