In 2015, the evangelical Wheaton College fired Larycia Hawkins, a political science professor, for taking a stance of solidarity with Muslims against hateful rhetoric. Ostensibly this was because Hawkins, a black woman, had contravened the college’s statement of faith by suggesting that Christians and Muslims worship the same god. Unofficially, it’s easy to see as a reaffirmation that evangelical Christianity is a religion only for bigoted white people.

At the time, a Wheaton graduate named Russell Vought defended the college’s decision:

Vought, an alumnus of Wheaton, wrote a blog post last year expressing support for his alma mater. He quoted a theologian who said non-Christians have a “deficient” theology but could have a meaningful relationship with God. Vought disagreed.

“Muslims do not simply have a deficient theology,” Vought wrote. “They do not know God because they have rejected Jesus Christ his Son, and they stand condemned.”

This intra-theological dispute has become relevant again because Vought was nominated to a deputy post at the Office of Management and Budget. At his confirmation hearing, Bernie Sanders made an issue of it:

Sanders brought up the passage, again and again, in the hearing. He asked Vought if he thought his statement was Islamophobic.

“Absolutely not, senator,” Vought said.

“Do you believe people in the Muslim religion stand condemned?” Sanders asked. “What about Jews? Do they stand condemned, too?”

“I’m a Christian,” Vought repeatedly responded.

“I understand you are a Christian,” Sanders said, raising his voice. The senator is Jewish and has said he’s not particularly religious. “But there are other people who have different religions in this country and around the world. In your judgment, do you think that people who are not Christians are going to be condemned?”

Some conservative outlets claimed that Sanders’ questioning was an unconstitutional “religious test”, which is of course utter nonsense. That clause of the Constitution refers only to job descriptions requiring that a public official be of a specific faith. When it comes to confirming a nominee, individual senators can vote any way they want for any reason they want (and I think there’s good reason to vote against all of Trump’s nominees anyway).

That said, as an advocate of separation of church and state, I’d be lying if I said this didn’t trouble me just a little. For what it’s worth, I agree it’s not a good precedent to judge someone’s fitness for a government job by their religious beliefs.

On the other hand, it’s not as if the religious right needed the excuse. Discrimination against open atheists is rampant in American politics. Conservative Christians have wielded “atheist” as a smear against progressives and reformers since the founding of this country. They’ve shamelessly demonized us as evil, untrustworthy and unfit for office. If they don’t like it when the shoe is on the other foot, they should start by apologizing for their own history of appeals to prejudice and pledging that they won’t resort to this tactic ever again.

When it comes to filling government jobs, we should not discriminate on the basis of religion. But it is a perfectly permissible and constitutional aim to keep hateful bigots out – people whose beliefs render them incapable of respecting the principle of equal protection under the law. If there are religious beliefs that have that effect, like a belief in white supremacy or female subordination, those would be valid reason to oppose a nominee.

So here’s the larger question: Is Hell an inherently hateful belief? If we follow Sanders’ logic to its conclusion, would this mean that no one who believes in eternal damnation can serve as part of the government?

I’m not necessarily saying this is the wrong conclusion, but that rule would keep out an awful lot of people, and not just Christians. For example, the activist group Muslim Advocates sent this letter opposing Vought’s nomination:

Mr. Vought has denigrated American Muslims and the Muslim faith. His writings demonstrate a clear hostility to religious pluralism and freedom that disqualify him for any appointment, including that of deputy director of the OMB.

I understand why Muslims would protest the appointment of a fundamentalist like Vought. They have reason to worry that someone who believes as he does would be biased against them and might enact that bias in his official duties.

But let’s be fair here: belief in Hell is part of Islam too. The Qur’an describes it in even more vividly sadistic detail than the Bible does. Isn’t it hypocritical to criticize someone for holding a belief which your own religion also teaches? If Christians who believe in eternal torture for nonbelievers should be barred from government jobs, we’d have to exclude Muslims on the same basis.

Now, you could argue that all this is irrelevant, because theology doesn’t map onto political beliefs in a one-to-one fashion. For example, there might be people whose belief in Hell makes them more compassionate and devoted to good government. They might want everyone to be healthy and the world to be peaceful, so that nonbelievers could live as long as possible and have the most opportunities to find salvation.

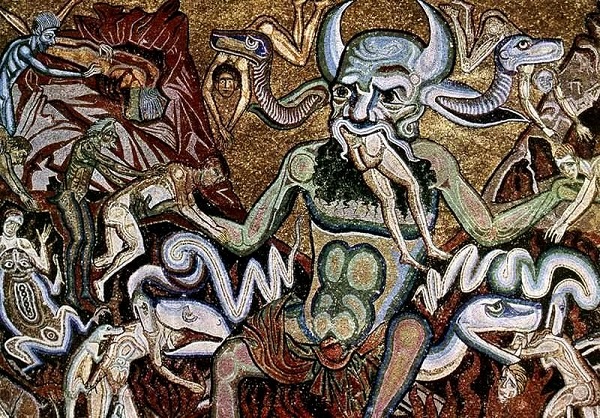

Hypothetically, it’s possible. But in practice, that’s usually not how it works. Belief in a cruel god makes a cruel man. If you believe that the supreme source of goodness sees most human beings as deserving of eternal torture, that can’t help but color your views of them. It’s also all too easy to imagine that someone who believed salvation depends on the “correct” beliefs would try to use state power to coerce others into adopting those beliefs – just as inquisitors and theocracies throughout history have done and are doing.

Given the balance of probabilities, if I had a vote on a nominee with beliefs like this, I wouldn’t disqualify them out of hand, but I’d want strong evidence that they’re willing to respect the secular principle and treat everyone equally. I realize that exclusionary theologies are common in Christianity and other major religions – but that doesn’t make them benign, it just means we often overlook how extreme they are. Wishing eternal torture on another human being is profoundly evil, even if most people who hold this belief never stop to think through the implications.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons