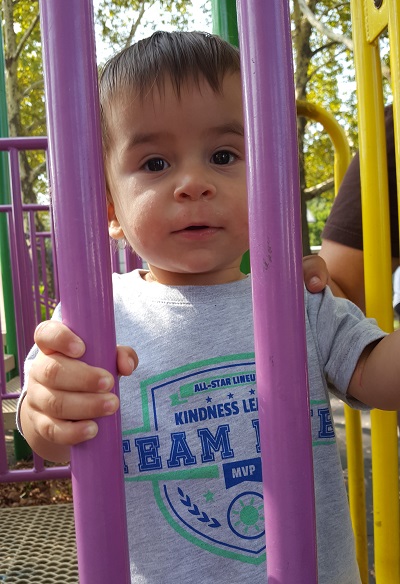

Now that I’m a parent, I’ve become more sensitive to marketing aimed at children, and I don’t just mean TV commercials. In line with the old Jesuit maxim, religion tries very hard to get its hooks into young, impressionable minds, and I’m seeing some of those attempts firsthand. A few have even gotten into my own household, like this glurge-y music box:

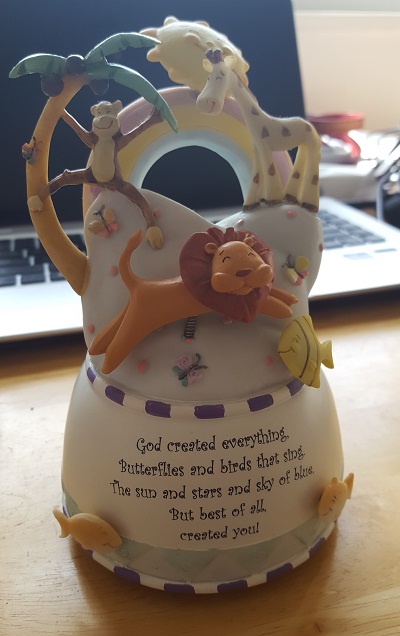

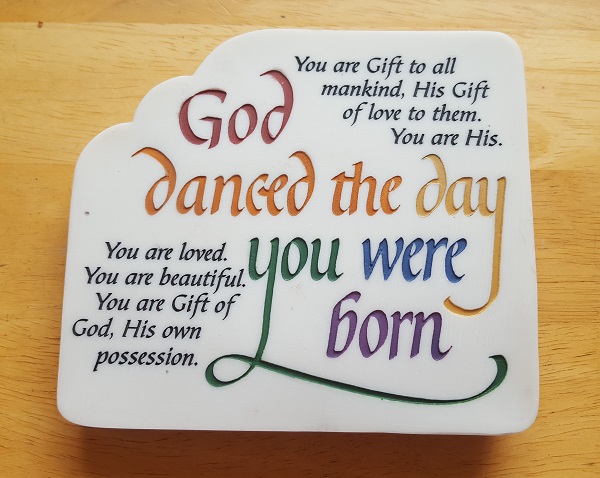

Or this plaque, which creepily tells children that they’re God’s possession:

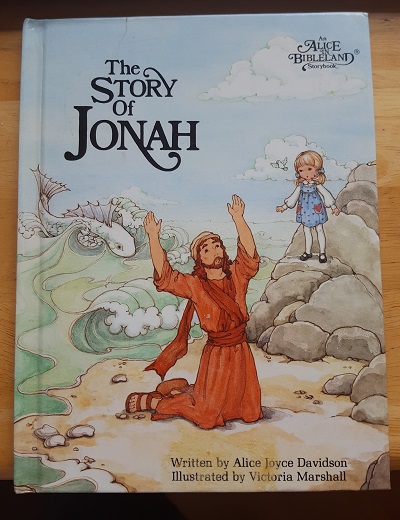

Or an even more cloying kids’ book that lectures its readers to always blindly trust that God has a plan and to never, ever question or doubt:

If you’re wondering why I have these, they were presents from my wife’s relatives. We’ve gotten tons of gifts and hand-me-downs, most of which were helpful, but there were a few things like these in the mix. I have to assume the gift-givers didn’t realize how they’d be received.

It’s not that I hide my atheism, far from it. I referenced it in my vows at our wedding, and it would be obvious to anyone who looked at the bookshelf in my living room.

But I also don’t make a point of spontaneously declaring it in every conversation. In spite of our less-traditional wedding, some of Elizabeth’s extended family members may have assumed that she’s retained the Catholicism she grew up with. (Nope.) Or they just treat belief in God as such an unquestioned norm, it’s never crossed their mind that anyone else might not think the same way.

Either way, I’m not offended so much as lightly amused. I don’t think there’s any ill will or passive-aggressiveness here. The people who gave us these gifts thought they were being helpful. But they’re obviously out of step with how I plan to raise my son.

To be clear, I’m not going to keep him ignorant of religion. On the contrary, I want to teach him all about it, so these ideas won’t be new to him when he encounters them in the wider world. But I’m going to present them in a neutral context, as things that some people believe and others don’t. More importantly, I want him to know about the true diversity of religious belief through history, all the different pantheons and mythologies that human beings have imagined.

I’m going to tell him that ancient people didn’t understand things like what causes the weather, or why we get sick, or why there are seasons, and were afraid because they didn’t understand. To make themselves feel better, they told each other stories about powerful, invisible people who control nature. They came to believe if we do things to make those invisible people happy, they’ll make good things happen for us.

But we have better explanations now. We’ve learned about things like the hydrological cycle, or germ theory, or axial tilt. The best part is that these aren’t just stories that someone made up, but real explanations you can test for yourself. You can see clouds moving on radar, or watch germs in a microscope, or fly around the world and see that the seasons are different. We’ve learned that our universe has rules, which we call natural laws, and we’ve never found proof of any of these invisible people.

None of this is to say that I intend to indoctrinate my son. I’m going to teach him what I think and why, but I’ll always encourage him to think for himself and respect his freedom to make up his own mind.

This is a distinction that religious evangelists usually fail to grasp. The article I quoted earlier thinks it’s scoring a point by noting that atheists write kids’ books too:

Good! Then we are all agreed! ‘Indoctrination’ isn’t ‘sinister.’ Transmitting the beliefs, values, and perceptions of one generation to the next is an important and unavoidable necessity that must take certain definite forms because of the nature of who we are transmitting them too: children.

This is wrong. “Indoctrination” doesn’t just mean “any effort by adults to teach their beliefs to children”. It describes a specific way of teaching which attempts to foreclose any questioning or doubt. It’s no surprise that religious proselytizers who rely on indoctrinating children would want to muddle this distinction.

In the years I’ve been writing for Daylight Atheism, I’ve collected many examples of what indoctrination, as opposed to education, looks like. It’s the religious textbooks that tell children to “keep a closed mind“, or the preachers who say to “choose faith in spite of the facts“, or the authorities who preach that obedience trumps all other virtues. It’s the religious parents who try to isolate their children from outside sources of information, tell them that parental love is conditional, or threaten them with eternal torture if they reject the beliefs they were raised with.

I’m taking these as examples of what not to do. I’ll never tell my son that he has to obey me without question. He needs some rules for his own benefit and safety, but I’ll always explain to him why the rules are what they are, and give him the chance to persuade me to change them if he thinks he has a better way. I’ll never threaten my son to make him agree with me, or try to conceal the existence of people who believe differently, or tell him I won’t love him if he doesn’t grow up believing exactly as I do.

While I’m trying not to indoctrinate him, I obviously hope that my son comes to see the world the same way I do. If he grows up to become religious, I can’t deny that I’ll be disappointed. But I’ll strive not to see it as a personal rejection. Everyone is a unique individual, and there are no guarantees in parenting. It’s not reasonable or fair to a child to expect them to echo all the beliefs of the previous generation.

I admit, in my more cynical moments, I’ve wondered whether my parenting philosophy puts me at a competitive disadvantage compared to religious fundamentalists. They don’t care about niceties like respecting freedom of mind or encouraging critical thinking. And while it takes brutal effort to squash a child’s native curiosity, it often works, in the sense of producing children who are ideological copies of their parents and afraid to question what they’ve been taught. I’m not saying I would ever do anything like this to my own son, my conscience wouldn’t permit me to, but does that mean that a good parenting philosophy is inherently less capable of propagating itself than a cruel one?

I don’t have an easy answer for this. All I can say is that indoctrination-based parenting, while it sometimes produces the desired result, also has a tendency to encourage children to rebel and go to the opposite extreme. It’s also a brittle worldview; as I noted, it requires blinding children to the existence of competing beliefs. More information and more diversity are both dangerous to it.

It may be that this worldview has frequency-dependent fitness: in a world of uniformity, it works, but in a more open and diverse society, it will crumble. Since we’re heading down the latter path, it gives me reason to believe that my approach may be both the most effective, as well as the most moral. It would be my greatest source of pride as a parent if my son not only led a happy and free life for himself, but made an example of his freedom for others to follow.