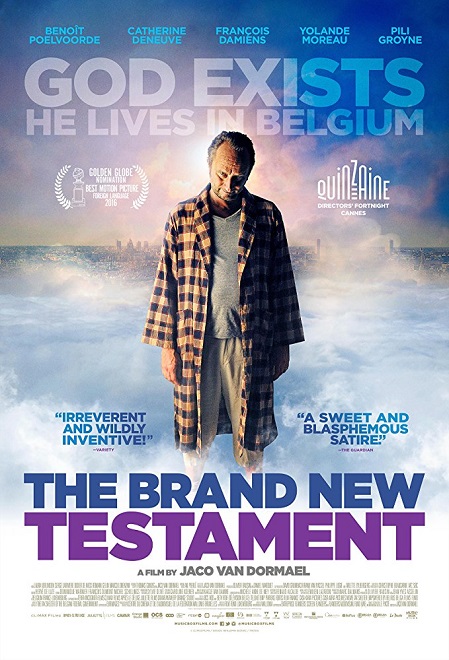

The Brand New Testament, a 2015 independent film from Belgian director Jaco Van Dormael, is a surreal, subversive comedy that parodies the theodicies dreamed up by religious apologists. When I heard about its premise, I had to see it for myself.

In Van Dormael’s vision, God exists, and he’s a cruel, foul-tempered old man, like a senior citizen who spends his time yelling at neighborhood kids to get off his lawn. He lives in a dingy, disheveled apartment somewhere above the city of Brussels, where he passes the time amusing himself by thinking up new ways to torture humanity.

He’s not interested in worship – he created all the world’s religions just for the amusement of watching people fight – but he seems to have gotten bored with holy wars and jihads. Nowadays, his focus is on creating “Laws of Annoyance” to make life more unpleasant in small ways, like that the other line always moves faster or that toast always falls butter-side down.

When God isn’t tormenting humanity, he’s being horrible to his long-suffering wife and his rebellious, intelligent ten-year-old daughter Ea (the young actress Pili Groyne, pitch-perfect). There used to be a fourth member of the family, the older son JC, but he renounced his father and fled the house long ago, and the patriarch decrees that he’s not to be spoken of anymore.

One day, Ea gets fed up with her father’s cruelty. While he’s passed out in a drunken stupor, she hacks into his computer, the source of all his power, and uses it to send every human being a text message with the exact date of their death. Then she escapes to Earth through a secret tunnel in the laundry room, where she sets about gathering a group of disciples and writing her own holy book, the titular Brand New Testament. Her mission is to tell everyone that there is no afterlife, that this world is the only paradise we have, and that we have to make the most of our finite lives.

When God discovers what she’s done, he erupts with rage. The uncertainty around death was one of the chief ways he kept humanity in a state of existential dread; when people know exactly how long they have to live, he has far less power over them. He follows Ea to Earth, determined to bring her back and force her to undo what she’s done.

Most of the film is devoted to six short stories, one for each of Ea’s six chosen disciples: a beautiful woman who believes she’s doomed to loneliness because she lost her arm in an accident; a bureaucrat leading a life of ennui until Ea rekindles his dream of exploring the world; a frustrated virgin who’s spent his life pining for a girl he met in his childhood; a psychopath who’s obsessed with death and killing; a woman in a loveless marriage who finds out her husband will outlive her; and a frail, terminally ill boy. Each of them tells their own story and the lessons they’ve learned. (These vary wildly in quality and tone. I thought the first and the last were strongest.)

In between the stories of Ea’s disciples, the rest of the movie shows the world’s reaction to her revelations, like TV newscasters reporting on the death dates (it’s dubbed “DeathLeaks”), or a YouTube-style video series by a daredevil who flings himself into increasingly suicidal stunts because he knows he can’t die for many years to come.

The other side plot is about God’s misadventures as he seeks his rogue daughter. Powerless on Earth, he finds himself repeatedly tripped up by the cruel laws he created, and beaten and abused by people who don’t take kindly to his domineering, do-you-know-who-I-am attitude. In one of the best scenes, he argues with a priest who doesn’t believe he is who he says. When the priest informs him of God’s command to love your neighbor as yourself, the cranky deity snaps, “I never said that. I hate myself. I would say hate your neighbor as yourself.”

Although Testament ends with the farthest thing imaginable from a sitcom-style family reunion, it has a remarkably upbeat and optimistic ending. It’s surreal, but never nihilist. And its moral gladdens my humanist heart. A movie that takes aim at God directly, rather than just parodying the absurdities of human belief, is something I’ve never seen before; I doubt it would have gotten made by an American studio.

It’s also an effective showcase for the director’s wild visual imagination. He conjures one image after another that stuck in my head: a man guiding a flock of birds with his hands as if conducting an orchestra; a disembodied hand gliding and twirling like an ice skater; a Narnia-like tunnel to earth hidden in a washing machine; tigers and giraffes wandering the deserted streets of Brussels; God’s office, its walls made up of endless rows of gloomy filing cabinets.

Some of the film’s vignettes land flat (if for some reason you wanted to see an amorous encounter between Catherine Deneuve and a gorilla, you’ve come to the right place). Its metaphysics were also a bit of a mystery (where did God’s wife and family come from, and why can Ea do miracles while her father can’t?). But I can overlook those faults in a film as creative, ambitious and as different as this.