I’ve written about the possibility of a post-work society, where there are more people than there are jobs for people to do. I’ve become more convinced that we need to start thinking and talking about this, because that society isn’t a far-off daydream. The robot era isn’t in the distant future, it’s happening now, all around us, and our lives are going to change faster than we think.

The optimistic view is that automation will benefit everyone. Robots will perform the drudge work, freeing up humans to engage in more creative work or to invent new industries. The pessimistic interpretation is that, while it’s happened this way in the past, we can’t expect that we’ll always come up with new jobs to replace the ones taken over by machines. There has to come a point where there just isn’t enough work for humans to do.

Now there’s a study that supports the disheartening conclusion. It finds that robots reduce human workers’ wages:

Each additional robot in the US economy reduces employment by 5.6 workers, and every robot that is added to the workforce per 1,000 human workers causes wages to drop by as much as 0.25 to 0.5 percent. Such are the conclusions reached by MIT’s Daron Acemoglu and Boston University’s Pascual Restrepo, who published their findings at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

…Acemoglu and Restrepo estimate that overall, for every 1,000 workers, an additional robot reduces the employment-to-population ratio by 0.18 to 0.34 percentage points, while also reducing wages by 0.25 to 0.5 percent. For context, the stock of industrial robots in the US increased fourfold during the period studied.

The jobs most at risk from robots (and AI in general) are “routine” jobs, where the work is by nature repetitive. Classically, this meant jobs like factory assembly lines. But as robots become more capable, they’re moving into white-collar and intellectual jobs that used to be the sole domain of humans, like telemarketing, law and accounting, which could mean displacing hundreds of thousands of workers:

Telemarketing, for example, which is highly routine, has a 99% probability of automation according to The Future of Employment report; you may have already noticed an increase in irritating robocalls. Tax preparation, which involves systematically processing large amounts of predictable data, also faces a 99% chance of being automated. Indeed, technology has already started doing our taxes: H&R Block, one of America’s largest tax preparation providers, is now using Watson, IBM’s artificial intelligence platform.

Robots will also take over the more repetitive tasks in professions such as law, with paralegals and legal assistants facing a 94% probability of having their jobs computerized. According to a recent report by Deloitte, more than 100,000 jobs in the legal sector have a high chance of being automated in the next 20 years.

Robots are moving into a wide variety of fields, like journalism: “There are applications that can write sports newspaper articles, based simply on the scoring history in the game.” Robots can also write financial stories.

I’ve written about how self-driving cars, already on the horizon, could replace millions of chauffeurs, taxi drivers and truckers, and how computer vision makes it possible for robots to sew clothes, putting garment workers out of business.

Even at the highest income levels, the robot transformation is coming. Deep-learning algorithms make it possible for robots to analyze X-rays and spot anomalies. And in an especially shocking example of how fast technology is improving, we could soon have autonomous robot surgeons:

In a robotic surgery breakthrough, a bot stitched up a pig’s small intestines using its own vision, tools, and intelligence to carry out the procedure. What’s more, the Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot (STAR) did a better job on the operation than human surgeons who were given the same task.

If we let this happen without making any effort to adapt, we’ll be facing a dystopia of inequality, where a small capitalist class owns the robots and the rest of humanity is permanently unemployed and impoverished. If we go down this path, the likely result is riots and social upheaval.

On the other hand, the solution isn’t to retard the advance of technology. We shouldn’t want a Luddite future where robots are banned just for the sake of preserving people’s ability to toil unnecessarily in make-work jobs. This technology has vast potential for uplifting humanity, creating wealth and material security and allowing for more leisure and more creativity, if only its benefits are shared broadly.

What we need, I’m becoming more convinced, is some kind of universal basic income where the “robot dividend” is paid out equitably across society. You can imagine a government that taxes robots and collects a share of the profits to distribute to all its citizens, something like the Alaska Permanent Fund. With the proceeds from a program like this, most people could work part-time, so that the minority of jobs which still need humans to do them are available to as many people as possible.

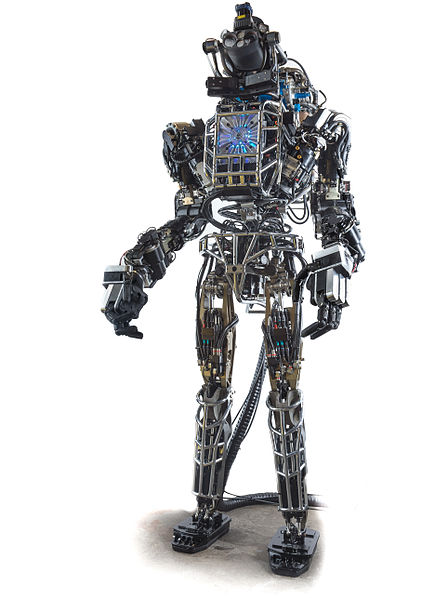

Image: The “Atlas” humanoid robot, built by Boston Dynamics and DARPA; via Wikimedia Commons