I’ve been reading a charming and informative book: Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything by Lydia Kang and Nate Pedersen. It’s a historical perspective on all the horrifying, mostly ineffective treatments that human beings have subjected ourselves to over the ages in a bid to cure disease and improve health.

The history of medical pseudoscience runs the gamut, from medieval doctors who thought that disease could be cured by bloodletting, blistering patients with hot irons, or purging by consuming poisonous antimony; to nineteenth- and twentieth-century Americans who gave their babies teething powders made with mercury, guzzled radioactive water for its supposed health benefits, and took toxic strychnine for an energy boost (or, ahem, male enhancement).

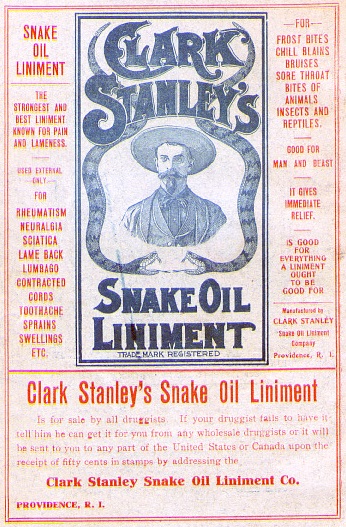

There was also a chapter on the origin of the term “snake oil”. I’ve used that phrase many times as an all-purpose descriptor for pseudoscience, but I never knew where it came from. It turns out, the real historical snake oil made its debut at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, by way of a hotshot salesman named Clark Stanley:

Dressed to the nines in a showy, frontiersman fashion, Stanley stood on a stage in front of the massing crowd and reached into a sack at his feet. He pulled out a rattlesnake, showing the audience its writhing, venomous body, then deftly slit the snake open with his knife and plunged it into a vat of boiling water behind him. As the snake fat rose to the surface, Stanley skimmed it off, mixed it into previously prepared liniment jars, and sold it to the crowd as “Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment.”

Like most patent-medicine salesmen, Stanley promised that his product would cure a dizzying array of ailments: “rheumatism, neuralgia, sciatica, lame back, lumbago, contracted cords, toothache, sprains, swellings… frost bites, chill blains, bruises, sore throat, bites of animals, insects and reptiles, etc.”

In his colorful (i.e., fabricated) autobiography, Stanley claimed to have learned the healing virtues of snake oil from Hopi medicine men. But the real story is more interesting. There was some actual science behind it, although highly distorted and misunderstood:

During the wave of Chinese immigration to the American West in the 1800s, Americans were alternately repelled and intrigued by traditional Chinese medicinal practices. Snake oil was a popular, and legitimate, topical medicine used by Chinese laborers to relieve pain, reduce inflammation, and treat arthritis and bursitis. Chinese snake oil, made with the fat of Chinese water snakes – high in omega-3 fatty acids – was actually an effective anti-inflammatory.

But the problem with Chinese water snakes is they all live in China. So, once you run out of the snake oil you brought with you across the Pacific Ocean, what do you do next? You look for a local snake… Rattlesnakes, unfortunately, contain much less beneficial fatty acids, about three times less than your average Chinese water snake. So snake oil made from rattlesnakes was not nearly as effective.

So even if Stanley had been selling genuine rattlesnake oil, it wouldn’t have had the curative properties he promised. But it turns out he wasn’t even doing that much, as federal investigators found in 1917 when they invoked the Pure Food and Drug Act to seize and analyze a shipment of his oil:

[An] official inquiry finally revealed the contents: mineral oil, beef fat, red pepper, and turpentine. Although that was good news for rattlesnakes, it was bad news for Stanley’s many consumers, who had been duped by the world’s first snake oil salesman.

The self-dubbed “Rattlesnake King” pled no contest and was fined a whopping $20, but it hardly mattered. By this point, he had been in business for over two decades and had done very well for himself. He exited the pages of history a wealthy man, but he bequeathed us a term that’s come to represent fictitious cure-alls of all kinds.

Truthfully, it’s hard to blame people for turning to quackery in eras where there were no real alternatives. Although we look back on the past with mingled horror and amusement, the fact is that for most of history we were powerless to cure things that didn’t get better on their own. And when that happens, there will always be quacks waiting to step in and fill the gap. Desperation and greed are a dangerous combination.

But we shouldn’t think too highly of ourselves, compared to our forebears. Just like them, we’re often operating on painfully limited and imperfect understanding. We’re only just beginning to understand human biology well enough to fix all the things that ail us. It’s irresistible to wonder what treatments we use today that will be similarly horrifying to future, more enlightened generations.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons