Summary: Why people don’t believe that the world is getting better.

If you believe, as I do, that moral progress is real and worth celebrating, you have a dilemma. Until now, the best-known exponent of that idea is Steven Pinker. And while I still believe Better Angels is a valuable book and most of its arguments hold up, its author has some questionable political views and an unsavory alliance with the right wing.

For those of us who’d like to make the case for progress without the taint of the “intellectual dark web”, an alternative has emerged: the book Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World – and Why Things Are Better Than You Think, by Swedish public health professor Hans Rosling. Sadly, he died of cancer just before it was published, but it was completed by his longtime collaborators, his son Ola Rosling and daughter-in-law Anna Rosling Rönnlund.

Rosling opens with a multiple-choice quiz about human development. It asks about topics like average life expectancy, population trends, deaths from natural disasters, or girls’ education. (You can take it yourself before reading any further.)

If you scored poorly, you’re in good company. Rosling writes that he’s given this quiz to audiences of highly educated, cosmopolitan people – scientists, politicians, corporate CEOs, journalists and skeptics – and almost every time, most people get a majority of the answers wrong. In fact, we score considerably worse than chance.

Why is this? It seems people consistently imagine the world as poorer, more violent and more chaotic than it is. In reality, for almost every one of Rosling’s questions, the correct answers are the most optimistic ones.

The purpose of the book is to explain why people do this. Each chapter describes a fallacy or a habit of thinking that leads us to overlook progress while focusing on the bad things that still happen, then debunks it with evidence.

For instance, the first chapter is about the “gap instinct”. Rosling writes that we have a habit of mentally dividing the world into “developing” and “developed” countries as if they were two islands separated by a chasm. Like looking down from the top of a skyscraper, the prosperous citizens of the West see everyone else far below them, and assume they must all be living on the same low level.

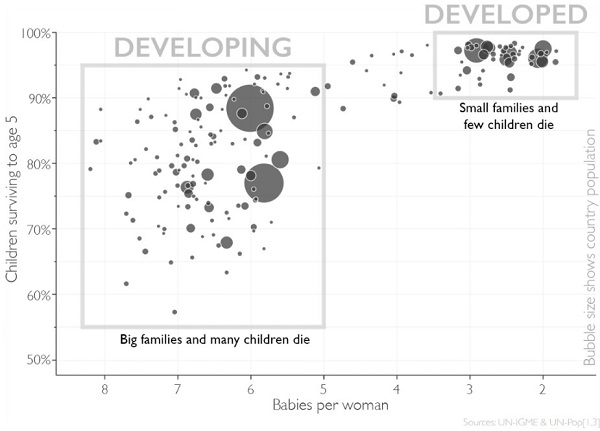

This is an inaccurate way of thinking, which the book demonstrates in one of my favorite examples. It shows a chart that graphs number of babies per woman against child mortality, with the size of the dot indicating the size of the country. It seems to show that wide separation between the developing and the developed worlds:

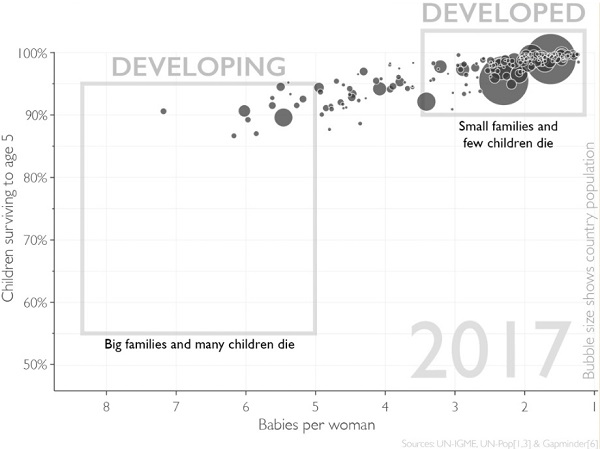

There’s just one problem: this graph is from 1965. This is what the world looks like today:

That gap no longer looks so large or so uncrossable. Almost every country in the world has made major progress at reducing early childhood deaths, moving up and over into the “developed” box. (One example that startled me: Egypt’s child mortality rate today is 2.3%, lower than France’s or the UK’s was in 1960.)

Rosling says that similar graphs could be drawn for a wide variety of developmental metrics: literacy, electrification, vaccination, childhood education, income levels, amount of land devoted to environmental conservation, number of scientific publications. As recently as the 1960s, a majority of humanity lived in poverty, but in just the last few decades, the world has gotten much better in almost every respect.

Rather than just two, he argues that it makes more sense to view the world as consisting of four levels of income, spanning the range from subsistence agriculture to modern industrialization. If you accept this classification, 75% of humanity lives in the middle, on levels 2 and 3.

And this makes a difference, because each step up means real improvements in quality of life.* On the book’s companion website, Dollar Street, you can see photos and read interviews with people from around the world who are living at these income levels.

In the last few decades, billions of people have moved up through these levels, refuting those who claim that poverty is an immutable state fixed by religion or culture. Rosling illustrates how his own country, Sweden, moved up the levels by citing his own family history. In 1873, when his great-grandmother was born, Sweden was a level 1 country; she and her family slept on a mud floor in the winter. In the 1920s, when his grandparents were alive, it had moved up to level 2: they no longer had to sleep on the floor, but they still lacked indoor plumbing, and his grandmother washed clothes by hand for her family of nine. In 1948, when he was born, it was a level 3 country; he was the first member of his family to attend university. During his lifetime, it moved up to level 4, with the generous welfare state we now think of as typical for Scandinavia.

And as countries move up the levels, their population naturally levels out, in what Rosling calls the most important trend of our time. When medicine improves, people no longer have to have lots of kids to ensure that some will survive; and as people escape poverty, they no longer need big families to work the farm or to be their old-age safety net. The current trend of fast population growth is a transitional stage, but one that’s already drawing to a close as standards of living improve. Even religion doesn’t affect this as much as you might think. As people become more educated and prosperous, they all desire smaller families, regardless of cultural beliefs.

Today, Muslim women have on average 3.1 children. Christian women have 2.7. There is no major difference between the birth rates of the great world religions.

Important to note, the book isn’t all sunshine and rainbows. Rosling devotes the final chapter to five global risks that concern him: climate change, global pandemics, financial collapse, world war and extreme poverty. However, he stresses that “things can be bad and getting better”. He calls himself not an optimist, but a “possibilist”: “someone who neither hopes without reason, nor fears without reason”.

Everything is not fine. We should still be very concerned. As long as there are plane crashes, preventable child deaths, endangered species, climate change deniers, male chauvinists, crazy dictators, toxic waste, journalists in prison, and girls not getting an education because of their gender, as long as any such terrible things exist, we cannot relax.

But it is just as ridiculous, and just as stressful, to look away from the progress that has been made.

He counsels against surrendering to despair or panic or turning to radical measures out of a false belief that nothing else will suffice. We still have problems, but we know how to solve them. It’s just a matter of rolling out the solutions that are already working.

* If you doubt this, Rosling gives an anecdote from his own experience that shows how a small amount of modern convenience can hugely improve the overall quality of one’s life:

“I was four years old when I saw my mother load a washing machine for the first time. It was a great day for my mother; she and my father had been saving money for years to be able to buy that machine. Grandma, who had been invited to the inauguration ceremony for the new washing machine, was even more excited. She had been heating water with firewood and hand-washing laundry her whole life. Now she was going to watch electricity do that work. She was so excited that she sat on a chair in front of the machine for the entire washing cycle, mesmerized. To her the machine was a miracle.

It was a miracle for my mother and me too. It was a magic machine. Because that very day my mother said to me, ‘Now, Hans, we have loaded the laundry. The machine will do the work. So now we can go to the library.’ In went the laundry, and out came books.

…Two billion people today have enough money to use a washing machine and enough time for mothers to read books – because it is almost always the mothers who do the laundry.”