Since I last wrote about it, COVID-19 has become a global pandemic. It’s spreading exponentially, infecting nearly all the world’s countries, including the U.S., no thanks to Trump’s staggering incompetence.

I never thought that the drastic quarantine measures taken by China would have been tolerated in Western democracies, but I was wrong. What was once unthinkable has become accepted virtually overnight. Italy and Spain’s governments have locked down their entire countries, and the U.S. is close behind them. In New York, where I live, all bars, restaurants and gyms have been closed and large gatherings of people have been banned. My day job has switched to work-at-home indefinitely, and public schools, including my son’s preschool, are shut down for at least a month. (If you see me posting less on the blog, it’s because I’m spending more time entertaining an energetic 3-year-old.)

In my own family, we’ve stopped dining out and curtailed our travel plans, and the Unitarian Universalist church we attend has switched to online-only. In just the last few days, life has assumed an eerie calm: peaceful, but with distant clouds of anxiety on the horizon, as if we’re waiting for an invading army or for a disaster to strike. I don’t personally know anyone who’s been infected, but I’m sure it’s only a matter of time.

At first, I thought these quarantine measures were too little, too late. Clearly, the virus is already spreading out of control, and we can’t isolate everyone from everyone else. But some news stories I’ve seen, especially the website FlattenTheCurve.com, convinced me that I was wrong. Self-quarantine and social distancing can help fight this pandemic.

Even though COVID-19’s death rate, estimated at between 2% and 3.5%, is much higher than the flu, it’s still true that the vast majority of people who contract it will recover on their own. But some people will become critically ill and will need mechanical ventilation. If there’s a surge of millions of cases at once (and of course, it’s not just COVID-19 we need to care about, it’s car crashes and gunshots and heart attacks and regular seasonal flu), there won’t be enough hospital beds. The health care system will be swamped and doctors will have to make terrible choices about who gets treated and who doesn’t. This has already happened in Italy.

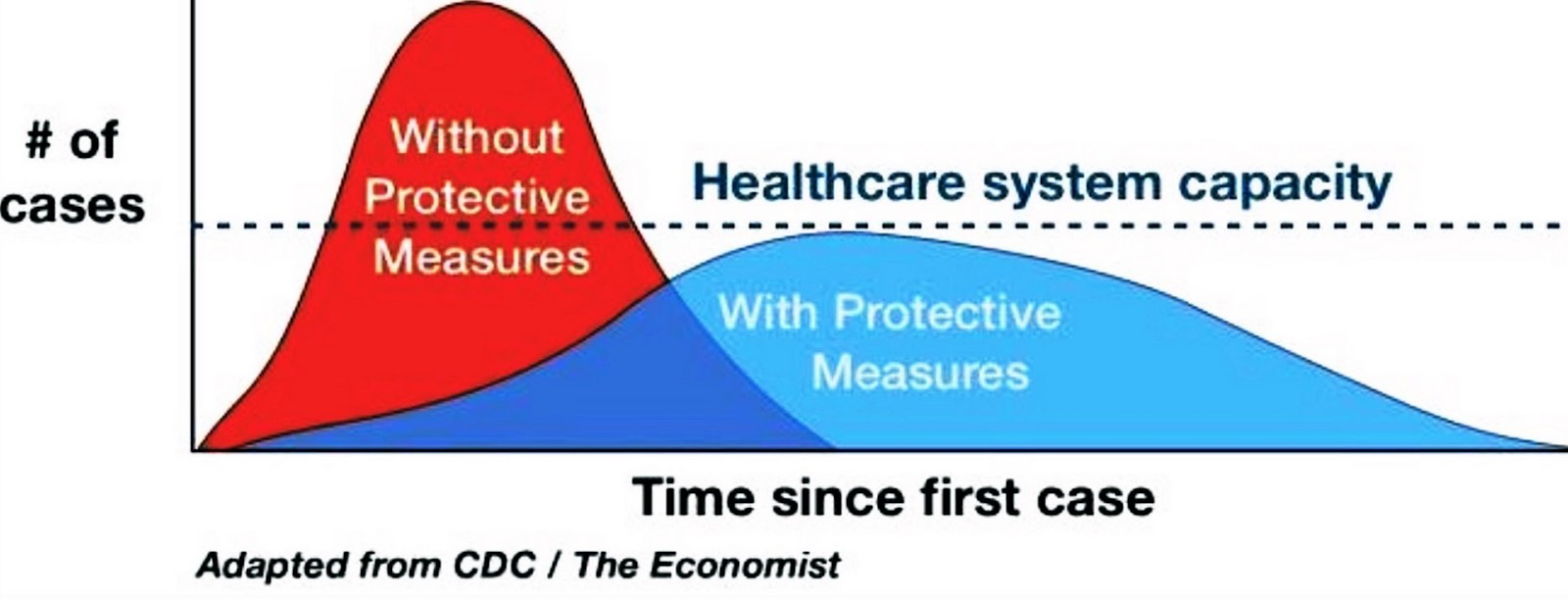

The idea of social distancing is that we can slow down the epidemic by enough that, even if there are the same total number of cases, they’ll arrive more slowly and be more spread out, so the health care system isn’t overwhelmed. Or, more realistically, it will be less overwhelmed and doctors won’t have to make quite as many life-or-death triage decisions.

For people who are younger and in good health, the coronavirus isn’t necessarily a deadly threat. But that attitude can breed dangerous complacency, because if we blithely go about our business, we can spread it to people who are older, who are immunocompromised or who have other lung ailments. We all have to make some sacrifices for the common good, to protect those who are most at risk. And by definition, any quarantine that’s wide-reaching enough to be effective will feel excessive, because it has to halt the contagion before it becomes widespread. If we wait until it’s obvious that we need to close restaurants (or schools or gyms or concert halls), it will be too late.

We have historical precedents for this. In 1918, while a flu pandemic was raging, Philadelphia went ahead with a parade to raise money for World War I, scoffing at public health concerns:

Writing in Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, the historian Thomas Wirth explains what happened: “On September 28, despite the increased infiltration of the disease among the civilian population, a rally for the Fourth Liberty Loan Drive proceeded with minimal debate about the repercussions for public health.” The head of Philadelphia’s Naval Hospital told the Public Ledger in the days before the parade: “There is no cause for further alarm. We believe we have it well in hand.” So, the parade went forward. “In the streets of downtown Philadelphia 200,000 people gathered to celebrate an impending allied victory in World War I. Within a week of the rally an estimated 45,000 Philadelphians were afflicted with influenza.”

…Soon hospitals were at capacity, as were the morgues and cemeteries. In a study published in 2009 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on the incidence curves of the 1918 epidemic in Philadelphia, researchers note that, 72 hours following the parade, all the beds in the city’s 31 hospitals were filled and by “the evening of October 3, the closure of schools, churches, and places of public amusement was adopted by the Philadelphia city council.” (source)

Meanwhile, St. Louis closed public places and banned large gatherings as soon as the flu struck, and their efforts paid off:

The city’s health commissioner and mayor ordered all theatres, schools, moving pictures shows, billiard halls, churches, Sunday schools, cabarets, lodges, societies, public funerals, open-air meetings, dance halls and conventions closed until further notice. The mayor knew there would be economic loss and inconvenience, but the situation was “so alarming” he had to act.

The 2007 study confirmed that St. Louis’s early intervention had its desired effect. In Philadelphia, the peak weekly excess death rate was 257 deaths per 100,000 people. In St. Louis, when restrictions were in place, the peak excess death rate was 31 deaths per 100,000 people. (source)

We should take every precaution, but we shouldn’t give in to panic, much less hoard masks or toilet paper. As I said last time, this isn’t the end of civilization. There will be suffering and hardship, but humanity will make it through this crisis. We’ll be able to tell our kids and grandkids stories about these days, the same way our elders had stories about polio or smallpox.

The first wave of this will be the worst. If it makes a recurrence, many people will have had it already and recovered, so there will be herd immunity to slow the spread. Many viruses evolve to be less deadly over time, because diseases that kill too fast are less effective at spreading themselves and are selected against. And with every biotech company in the world working furiously on the problem, we can be confident that a treatment or a vaccine will be discovered. (We need all the brainpower we can get!)

Until then, the best thing we can do is stay home. It’s not a punishment, but a collective gesture of compassion for the most vulnerable. Thankfully, we have the internet to make this time more bearable. We have blogs and e-books (ahem!) and movies and music and art, and we can be present, virtually, with and for each other to keep our spirits high.

Image credit: flattenthecurve.com