I’m going to vote for Joe Biden in November to save this country from fascism and kleptocracy, but I’m not thrilled about it.

In the interest of transparency, my first choice was Elizabeth Warren. I thought she was exactly what Democratic candidate should be: supremely intelligent and well-prepared, strongly progressive, and a ferocious debater (her annihilation of Mike Bloomberg was exactly what I wanted to see her do to Donald Trump). But other Democratic voters clearly didn’t agree with me, since she didn’t win a single state.

When she dropped out, Bernie Sanders was my second choice. And after the first three contests, he was the clear frontrunner. But after the South Carolina primary and Super Tuesday, Joe Biden surged into the lead and Sanders never came close to catching him again. What went wrong?

You could say that the Democratic electorate is laser-focused on “electability” this year, but that’s really just restating the question in different words. Why didn’t voters consider Sanders or Warren “electable”, whatever that means?

The way I see it, Bernie Sanders’ theory of how he could win the nomination had three parts:

1. A multiracial coalition of progressive young people who’d be his core voting bloc;

2. Blue-collar white voters who are socially conservative but economically liberal and would be attracted to Sanders’ kitchen-table populism, siphoning off votes from Republicans;

3. An influx of new voters who were disaffected and cynical about politics and didn’t participate in the past, but would see that Sanders was unlike other politicians and would enter the race to support him.

It was a good theory, and I can see why he thought it would work. If it had come true, I’d have been in the Sanders camp without reservation. Unfortunately, it failed on all three counts:

1. Young voters didn’t show up in the numbers that Sanders needed to win. The 18-to-44 demographic did support him by a wide margin, but exit polls found that youth turnout in a majority of states was flat or – even more surprising – down compared to 2016.

2. Those white voters were never economically populist. In the 2016 primary, Sanders won a slew of Midwestern states like Minnesota, Oklahoma, Kansas, Indiana and Michigan. He used this to argue that these mostly-white voters of these states weren’t as conservative as had been assumed, that they weren’t attracted to the more centrist brand of politics that Hillary Clinton advocated, and that there was a pent-up, unrecognized desire for radical change.

Unfortunately, 2020 disproved that theory. The second time around, these states went solidly for Biden. As Amanda Marcotte writes, it’s very likely that the explanation is sexism. Sanders’ 2016 victories were, in reality, the most conservative Democrats casting a protest vote against a female candidate. When those voters didn’t have to choose between a woman and a white guy, they switched overwhelmingly to the more conservative white guy in the race.

3. There was no surge of new voters. This is the fact I found the most personally surprising. Democratic turnout is up compared to 2016, but it’s benefiting Biden. I didn’t see that coming at all.

It’s worth noting that this result disproves “accelerationist” theories, bandied about in 2016 by irresponsible people, that Donald Trump’s election would be a good thing because it would intensify people’s suffering to the point where it was unbearable and would bring the revolution that much sooner. They were only half right: Trump’s election has caused enormous suffering and hardship, but it hasn’t brought a surge of new voters or made the people who do vote significantly more progressive.

A hard truth that I think we progressives need to face is that there’s no huge reservoir of democracy-curious voters who could be activated by the right candidate. There are millions of Americans who don’t vote, but the reason isn’t that they’re waiting for a candidate who’s not like those other politicians to swoop in and sweep them off their feet. They don’t vote because they genuinely don’t care about politics, no matter what views a candidate advocates. There is voter suppression, and that can make a difference in a close race – but for the most part, everyone who wants to vote already does. (I’d analogize this to baseball: the reason I don’t watch baseball isn’t because I haven’t found the right player who’ll get me excited, but because the game itself doesn’t interest me.)

The other hard truth is that, as much as you or I might think Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren has far better political views, we’re in the minority even among Democrats. (FiveThirtyEight says: “At most, the liberal wing of the Democratic Party amounts to about a third of the primary electorate.”)

You can rage against this, and you can wish it were other than it was. I do. But if you’re reading this post at all, you’re part of a politically aware (and if I were in the mood for self-congratulation, I might add “enlightened”) minority. To win, a candidate can’t just pander to us. They have to appeal to a broad swath of the electorate.

You can analogize this to the way movies are marketed. Hollywood studios classify the viewing public into four broad groups: older men, older women, younger men and younger women. A movie that appeals to all of them is a “four-quadrant” blockbuster.

In that sense, Barack Obama was the four-quadrant Democratic candidate. He inspired a huge coalition that included young voters, older black voters, mostly white white-collar professionals, and mostly white blue-collar workers. That coalition propelled him to a landslide victory in 2008 and a narrower but still decisive win in 2012.

Sanders, for all that I like him, is a two-quadrant candidate. He appealed to a subset of the Democratic electorate, mostly younger voters and white-collar professionals (again, like me). Unfortunately, his strongest demographics also tend to be lower-turnout and numerically smaller, and he was blown out among older black voters and blue-collar whites.

The reason this isn’t more widely recognized is that the demographics that Sanders appeals to are also the ones that are most active online. If you use social media, this bubble can create an illusion of false consensus: he must be winning, because “everyone I know” likes him. But there are demographics you’re not hearing from who are as large or larger. Unfortunately, this also feeds the conspiracy theory that more conservative Democrats keep winning because they’re stealing elections through fraud or DNC shenanigans.

To his credit, Sanders devoted considerable effort on outreach to black voters this time around, but he didn’t succeed in convincing them. You can debate whether this is because of their great affection and loyalty for Barack Obama, which successfully translated to his vice president; or whether it’s because black voters are more conservative and were turned off by Sanders’ policies; or whether it’s because, regardless of their own political views, they don’t trust Americans to vote for a very liberal candidate and believe Biden was the safer choice.

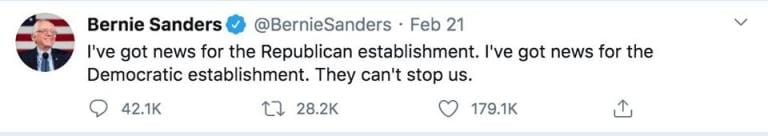

It probably didn’t help that Sanders made a habit of attacking “the Democratic establishment”, like in this tweet:

While this tactic fired up his most loyal supporters, it may have turned off a bloc of loyal voters, especially black voters, who consider themselves to be part of the Democratic establishment. To them, it sounded like an outsider plotting to swoop in and take over the coalition that they supported and helped to build. As this article puts it, “Sanders’s insurgent identity, his explicit decision to run as an outsider in order to appeal to habitual non-voters, may well have doomed him with this vital constituency.”

This isn’t the race I wanted, but there’s reason for progressives not to throw in the towel. As I’ve said before, all the 2020 Democratic candidates, Biden not excepted, are advocating policies well to the left of Barack Obama. Biden’s health-care plan isn’t Medicare for All, but it includes a public option that’s essentially a Medicare buy-in, which is highly popular and would be a big step forward just as Obamacare was.

And as this column by Jamelle Bouie argues, Biden is a creature of the party, for better and for worse. If we can win Democratic control of Congress (more important by far!), he’ll sign anything they pass. Bouie draws an analogy to Virginia, where the centrist governor Ralph Northam has agreed to major progressive policy changes put forward by a Democratic state legislature.

There’s one other thing that surprised me, which is that most Democratic officeholders in swing states prefer Biden. Of course, some of this might be due to party loyalty, but it’s also reasonable to believe that they know the composition and preference of their states better than anyone else. Their opinion shouldn’t be discounted – especially since polls also show Biden with the strongest lead in these states.

It’s worth remembering that, even with all the invented scandals, the sexism and other baggage dragging her down in 2016, Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by a wide margin and only lost by a hair-thin sliver in a few crucial states. Biden, who’s basically a male version of Clinton, could win those states decisively – especially with an economy that’s cratering, which always inspires a throw-the-bums-out mood among voters. If this comes to pass, it wouldn’t be the victory I wanted or hoped for. But if it pulls the country back from the edge of the abyss it’s teetering on, I’ll take what I can get.

Image credit: Susanne Nilsson, released under CC BY-SA 2.0 license