By James A. Haught

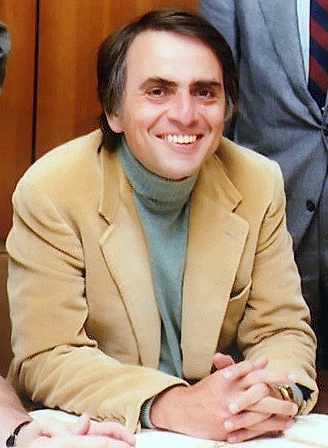

Astronomer Carl Sagan wrote a blunt attack on all forms of magical thinking. In The Demon-Haunted World, he assails:

Astrology horoscopes, faith-healing, UFO “abductions,” religious miracles, New Age occultism, fundamentalist “creationism,” tarot card reading, prayer, prophecy, palmistry, transcendental meditation, satanism, weeping statues, “channeling” of voices from the dead, holy apparitions, extrasensory perception, belief in life after death, “dowsing,” demonic possession, the “supernatural powers” of crystals and pyramids, “psychic phenomena,” etc., etc.

The message of his book may be summed up: Many people believe almost anything they’re told, with no evidence, which makes them vulnerable to charlatans, crackpots and superstition. Only the scientific outlook, mixing skepticism and wonder, can give people a trustworthy grasp of reality. Sagan scorns supernatural aspects of religion. Some of his comments:

“If some good evidence for life after death were announced, I’d be eager to examine it; but it would have to be real scientific data, not mere anecdote. Better the hard truth, I say, than the comforting fantasy.”

“If you want to save your child from polio, you can pray or you can inoculate. Try science.”

“Think of how many religions attempt to validate themselves with prophecy. Think of how many people rely on these prophecies, however vague, however unfulfilled, to support or prop up their beliefs. Yet has there ever been a religion with the prophetic accuracy and reliability of science? No other human institution comes close.”

“Since World War II, Japan has spawned enormous numbers of new religions featuring the supernatural. In Thailand, diseases are treated with pills manufactured from pulverized sacred Scripture. ‘Witches’ are today being burned in South Africa. The worldwide TM [Transcendental Meditation] organization has an estimated valuation of $3 billion. For a fee, they promise through meditation to be able to walk you through walls, to make you invisible, to enable you to fly.”

“The so-called Shroud of Turin is now suggested by carbon-14 dating to be not the death shroud of Jesus, but a pious hoax from the 14th century – a time when the manufacture of fraudulent religious relics was a thriving and profitable home handicraft industry.”

Sagan quotes the Roman philosopher Lucretius: “Nature is seen to do all things spontaneously of herself, without the meddling of the gods.”

And he quotes the Roman historian Polybius as saying the masses can be unruly, so “they must be filled with fears to keep them in order. The ancients did well, therefore, to invent gods and the belief in punishment after death.”

Sagan recounts how the medieval church tortured and burned thousands of women on charges that they were witches who flew through the sky, copulated with Satan, changed into animals, etc. He says “this legally and morally sanctioned mass murder” was advocated by great church fathers.

“Inquisitional torture was not abolished in the Catholic Church until 1816,” he writes. “The last bastion of support for the reality of witchcraft and the necessity of punishment has been the Christian churches.”

The astronomer-author is equally scornful of New Age gurus, flying saucer buffs, seance “channelers” and others who tout mysterious beliefs without evidence. He denounces the tendency among some groups, chiefly fundamentalists and marginal psychologists, to induce people falsely to “remember” satanic rituals they experienced as children.

Again and again, Sagan says that wonders revealed by science are more awesome than any claims by mystics. He says children are “natural scientists” because they incessantly ask “Why is the moon round?” or “Why do we have toes?” or the like. He urges that youngsters be inculcated with the scientific spirit of searching for trustworthy evidence, to guide them through “the demon-haunted world.”

This book of Sagan’s is more confrontational than his previous works. Perhaps, like Voltaire, he felt spurred by advancing age to take a public stand against mysticism.

Incidentally, while Sagan’s volume was reaching bookstores, all three of America’s national newsmagazines – Time, Newsweek and U.S. News & World Report – printed cover stories questioning Christianity’s chief miracle, the Resurrection.

The battle, it seems, is on.

(Haught is editor emeritus of West Virginia’s largest newspaper, The Charleston Gazette-Mail, and a senior editor of Free Inquiry magazine. This article originally appeared in Free Inquiry, spring 1997.)