Afghanistan has fallen, and the Taliban is back in power.

After the American pullout that Donald Trump negotiated* and Joe Biden followed through on, the Taliban retook the country in a matter of weeks. The U.S.-backed government folded with scarcely a fight, and the president, Ashraf Ghani, fled the country as the Taliban closed in on Kabul.

While this outcome wasn’t surprising, it seems that no one expected the Taliban to reconquer the country as quickly as they did. There was an ignominious scramble to get out as they approached the capitol, with some refugees clinging to the sides of planes. The U.S.’ biggest shame is that we didn’t do more to help evacuate the brave people who put their lives on the line for us.

There’s no mincing words: the resurgence of the Taliban is a humanitarian disaster. This bleak and fanatical cult will once more hold the country in its grip, banning art and music, sports and movies. The hope for secularism and democracy has been crushed, and the book-burners and head-choppers will rule again. Girls like Malala Yousafzai will once again face death for wanting an education, and women will be returned to a state of subjugation.

And yet, I’m not convinced that a better outcome was ever possible. I don’t mean to sound cavalier about it, but… what else were we supposed to do?

We’ve been occupying Afghanistan for twenty years, a period spanning four presidential administrations of both major parties. But in all that time, we made no lasting difference. We could prop up a feeble client state, but it seems that was all we could do. We never did more than temporarily suppress the Taliban. All the lives we lost, all the money we spent, all the effort we poured into the nation-building project was just putting off the inevitable.

What was the alternative? Was the U.S. supposed to occupy the country forever, fighting an endless insurgency, sacrificing an unlimited amount of its own blood and treasure, for no benefit to us? It can’t be our responsibility to keep the peace in every trouble spot in the world.

If I thought there was a chance that our military occupation would transform Afghanistan and cause democracy and human rights to bloom, I’d be in favor of staying as long as it took. The cost would be worth it, just as it was worth it to rebuild Germany and Japan into liberal democracies after World War II.

But that showed precious few signs of happening in Afghanistan, and the U.S.’ resources are finite. At some point, we have to conclude the price is too high and the chances of a good outcome are too small. Unless we’re going to commit to permanent occupation, we eventually have to withdraw and let Afghanistan’s people choose their course for themselves. Again, it’s awful what’s going to happen, but we lack the power to compel every society on Earth to live as we want them to.

Whatever moral you take from it, the collapse of Afghanistan stamps out the last remnants of the post-9/11 neoconservative ideology: the dream that we could “make the world safe for democracy” by overthrowing repressive regimes and setting up pro-Western states patterned on the U.S. model, as if America were a Cracker Barrel franchise.

It was a goal that blended noble aspirations – for who could object, in the abstract, to freeing a people from the grip of rulers like Saddam Hussein or the Taliban? – with the sordid reality that what the neocons wanted most of all was a new American empire, with themselves the imperial rulers. Money and power were always the goal, and any progress in human rights or democracy was, at best, secondary. (Evidence of this grubby realpolitik is that the neocons never objected to alliances with equally odious regimes, so long as they were willing to provide a base for us to refuel our bombers. Saudi Arabia comes to mind.)

Democracy is a good thing, but it’s a contradiction in terms to speak of spreading democracy by force. Democratic government can take root and thrive only if the desire for it is organic; it can’t be imposed at the barrel of a gun. It was never plausible that a people “freed” by military invasion and occupation, wreaking havoc on their country in the process, would welcome the invaders. We were never going to be greeted as liberators. It’s very possible that prolonged occupation was turning people against us and our Western ideals, and that this is part of why the U.S.-backed military and government dissolved so rapidly. It never had popular legitimacy or popular support.

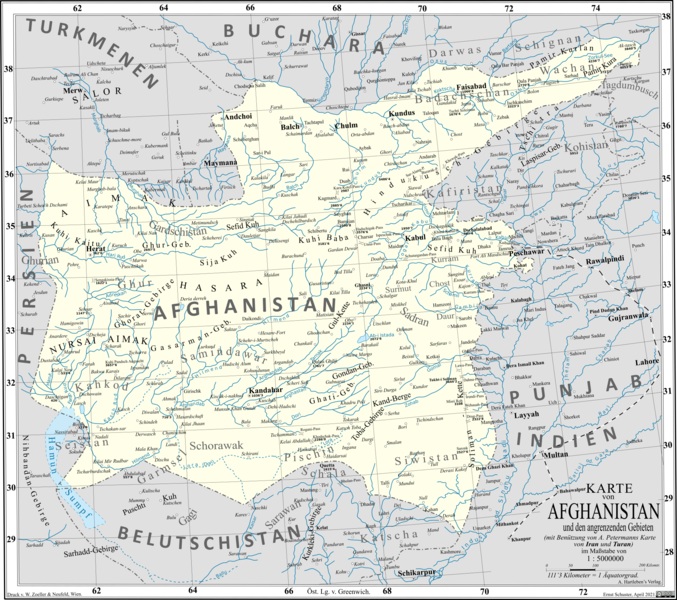

This isn’t to say that the Afghan people “weren’t ready for freedom” or any other offensive relativist trope. But I do think we were trying to impose a Western-centric notion of national identity that they don’t necessarily share. Many people of that region value ethnic and tribal ties above all else. “Afghanistan” isn’t an entity that commands their allegiance, much less something they consider worth fighting and dying for. To the extent that anything unites them, it’s Islam – which leaves an open road for the Taliban to claim legitimacy as representing the purest form of Islam, even if their interpretation of it is harsher than the locals might prefer. (A similar phenomenon can be seen in the United States of America in the way white evangelicals vote.)

The invasion of Afghanistan took place in the heat of the jingoistic fervor that swept the nation after 9/11. There was never a clear purpose to our presence there – except possibly for getting Osama bin Laden, which we did, only he turned out to be in Pakistan. But successive U.S. leaders continued the occupation, increasing the sunk costs, because to pull out would be like admitting the failure of the American imperial project. Each president kept kicking the can down the road just so the inevitable collapse wouldn’t happen on his watch.

Now we’re finally out, and although the end was ugly, I’m glad for it. The Taliban are monsters, and the world would be a better place without them in it. But there are many monstrous regimes in the world, and the U.S. isn’t omnipotent. We can’t get rid of them all, no matter how much we might wish to. We need more humility about the limits of our ability to reshape other societies in our image. It might keep us from getting into the next quagmire.

* Unsurprisingly, the RNC at first bragged about Donald Trump’s role in ending the war, then swiftly memory-holed it.