[Previous: We should all be working less]

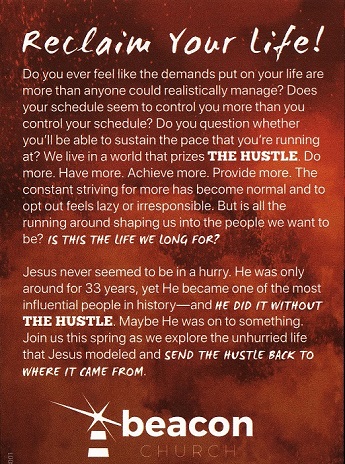

I got this flier in the mail from an evangelical church trying to drum up business:

This caught my eye, because it’s a rare case of churches actually trying to make themselves appealing. They’re testing a new and different message that they hope will resonate with younger generations. It’s a change of pace from the usual evangelical strategy of repeating the same message they’ve always used, and hoping it will work this time if they say it with the right intonation or print it in the right font.

Nevertheless, it falls short. Advertising 101 is to describe a problem, then sell the solution. This flier accomplishes #1, but not #2. It identifies “hustle culture” as something people might care about, but it doesn’t try to explain why attending their church would solve this problem.

If anything, it does the opposite. It’s asking busy, stressed, overwhelmed people to add another regular commitment to their lives. I attend a Unitarian Universalist church sometimes, and while it has other benefits, I’d never say it saves time.

A crisis of capitalism, not a spiritual crisis

It’s true that many of us feel overworked and burned out. Part of the reason is the decline of unions and the rise of the gig economy. The minimum wage hasn’t remotely kept up with inflation. Jobs that offered stability, benefits and long-term prospects have been replaced with jobs that are lower-paid, more unpredictable, and more precarious. Instead of taxi drivers making a regular hourly salary, drivers for Uber and other such companies get paid by the ride. The only way for them to earn enough to survive is to work around the clock.

Hustle culture has also come for white-collar workers, who are facing soaring home prices and crippling student debt. Even though workers in law, tech, medicine and other industries get big paychecks, those often come with an expensive, debt-laden lifestyle that consumes every dollar they make. As a result, they can’t afford not to work.

When a job loss would be catastrophic, workers feel the need to broadcast their absolute loyalty and devotion to their employers, hoping to be spared from layoffs. Often, they do this by bragging about how hard they’re willing to work, occasionally to a self-abasing or unhealthy level. For example, take Esther Crawford, an engineer at Twitter, whose scheme for surviving Elon Musk’s firing spree was to boast about sleeping in the office:

(Musk fired her too. So much for loyalty.)

Either way, hustle culture isn’t a spiritual crisis. It doesn’t exist because we’ve lost the sense of meaning in our lives and we’re trying to fill the void with work. It exists because we’ve lost the social safety net and people feel compelled to devote every waking minute to work for the sake of survival. In other words, it’s a crisis of capitalism.

It’s fitting that an evangelical church is hawking Jesus as the answer (somehow) to this. Evangelicalism is all about offering individual solutions to systemic problems. End racism by teaching people that Jesus loves everyone! Fix hunger by donating to church-run soup kitchens! Stop school shootings by bringing back prayer!

This flier continues that tradition. It’s the Christian-flavored version of a meditation app to help you relax, or a meal-delivery service for people too busy to cook. It’s a band-aid fix to slap on top of a bigger underlying problem.

Idle hands are the devil’s tools

Of course, massive inequality and laborers struggling to earn their bread aren’t new. That’s been the state of affairs for most of human history. It’s economic comfort and security that are the exceptions. For the most part, these conditions have only arisen in well-ordered democratic states with a strong notion of human rights.

Through the ages, Christianity has been the ideology of power. Accordingly, it’s been the ally of kings, emperors, feudal landlords, enslavers, and others who led lives of luxury while exhorting those beneath them to work. It’s been extremely useful to these overlords to teach the poor that they’ll be repaid in heaven for their toil on earth.

This is the origin of what we now call the Protestant work ethic. It’s the belief that hard work isn’t just a means to an end, but is beneficial to the soul. Conversely, if work is good, then rest and leisure must be bad for you—even sinful.

This message is woven throughout Christianity: whether it’s folk sayings like “the devil makes work for idle hands,” or classifying sloth—in other words, laziness—as one of the seven deadly sins, or using the Garden of Eden myth as a just-so story for why God expects us to suffer and toil. And the rich have put that belief into practice (though, of course, never applying it to themselves).

It’s historically been a widespread belief that the poor were morally deficient and should be made to work for their own good. As Bertrand Russell put it in “In Praise of Idleness“:

The idea that the poor should have leisure has always been shocking to the rich. In England, in the early nineteenth century, fifteen hours was the ordinary day’s work for a man; children sometimes did as much, and very commonly did twelve hours a day. When meddlesome busybodies suggested that perhaps these hours were rather long, they were told that work kept adults from drink and children from mischief. When I was a child, shortly after urban working men had acquired the vote, certain public holidays were established by law, to the great indignation of the upper classes. I remember hearing an old Duchess say: “What do the poor want with holidays? They ought to work.” People nowadays are less frank, but the sentiment persists, and is the source of much of our economic confusion.

Or American freethinker Robert Ingersoll, in the essay “Eight Hours Must Come“:

The working people should be protected by law; if they are not, the capitalists will require just as many hours as human nature can bear. We have seen here in America street-car drivers working sixteen and seventeen hours a day. It was necessary to have a strike in order to get to fourteen, another strike to get to twelve, and nobody could blame them for keeping on striking till they get to eight hours.

…The laboring people a few generations ago were not very intellectual. There were no schoolhouses, no teachers except the church, and the church taught obedience and faith — told the poor people that although they had a hard time here, working for nothing, they would be paid in Paradise with a large interest.

When it comes to hustle culture, the modern incarnation of this thinking, Christianity isn’t an innocent bystander. It bears a heavy share of the blame. What’s more, it’s still standing in the way of making life better.

Why the nonreligious support socialism

Historically, America has been an outlier among rich countries in how little we regulate the economy. Whether it’s the strength of our social safety net, the power of labor unions, or our legal protection for workers’ rights, we rank well below peer nations.

Our undemocratic electoral system plays a part in this, but it’s also true that Americans are more suspicious of socialism than voters in other industrialized nations. A common explanation is that American religiosity is also high for a wealthy country, and those beliefs stand in the way of progressive reform. The American brand of Christianity encourages a focus on private, individual salvation, which makes believers distrust anything that smacks of collectivism.

There’s data to support this hypothesis:

To understand the relationship between socialist values and religion, we used the 2013 Public Religion Research Institute’s “Economic Values Study.” As part of the survey, respondents were asked how much they agreed with a battery of statements regarding economic values, including “It is the responsibility of the government to take care of people who can’t take care of themselves,” The government should do more to reduce the gap between the rich and poor” and “The government should guarantee health insurance for all citizens.”

…In these data, those who agreed that social problems would be resolved if enough people had a personal relationship with God were 20 percent less socialist than those who disagreed. A worldview that pits faith directly against collective action explains clearly why collectivist efforts have traditionally foundered in the U.S.

If American Christianity has promoted an individualist mindset that undercuts support for socialism, then you’d expect that nonreligious Americans would be more receptive to appeals for economic justice. Indeed, that’s what the data shows:

By the same token, Americans who are not religious (sometimes called the Nones) would be those most likely to hold socialist values. And indeed, this is what we find: Nones are 10 percent more socialist, on average, than religious Americans.

You can’t beat a bad culture through individual choices. You need a different, better culture to do that. Specifically, we need a culture that frowns on overwork and values leisure and happiness as human rights. That’s the antidote to the toxicity of hustle culture. And that will never happen until we have a society that reins in the most egregious expectations of capitalism. It’s the growing political clout of the nones, not churches resorting to the latest buzzwords in their marketing pitches, that’s our best hope for creating a better future for ourselves.