I’ve said in the past, and will have occasion to say again, that the world is slowly becoming a better place despite the tragedies and outrages that parade before our eyes. But just because the overall picture is brightening doesn’t mean that there aren’t real and lingering dark spots that ought to command our attention. One is the continuing civil war in Syria and the exodus of people, mostly Muslim, it’s scattered across Europe and the United States.

Last month, I mused about the astounding hypocrisy of self-described Christians who cry louder than anyone else about the necessity of shutting out foreigners, aliens and refugees. Their faith, perhaps more so than any other, was built on stories of refugees seeking shelter in a hostile world, and yet they remain stubbornly oblivious to the lesson. The Syrian crisis may have brought this xenophobia to the fore, but it doesn’t originate in fears of terrorism. Before this, you’ll remember, the fear du jour was “illegal immigrants” – who, the demagogues repeatedly insisted, were bringing crime and drugs, living in indolence and leeching off honest taxpayers, stealing jobs that by right should have gone to “real” Americans. (The contradiction between those two last prejudices invariably goes unnoticed and unremarked-upon.)

The painful truth is that human nature will always seek out an enemy, an imaginary Other for us to draw ourselves in opposition to. This season, it’s the Syrians. The season before that, it was Mexicans and Central Americans. And before that, it was the Jews and the Japanese, the Irish and the Italians, the African-Americans and the Chinese. In another generation, no doubt, the lines will have shifted again and there will be some new menace which, for our own safety, we have to close the gates and raise the barricades against.

This tendency isn’t born in reason and doesn’t have its roots in cool and sober reflection. It’s something far more ancient and uglier, a dark and amorphous fear that coils around the human heart. Oh, it’s a canny enemy: it may wear a different mask every time it rises to the surface, it may present itself in a different guise, it may come prepared with careful and sensible-sounding reasons why this time is different, why this time we really are under threat and it’s necessary to contemplate the unthinkable. But it’s the same fear, nonetheless, and even when it’s vanquished, it can be counted on to rise again a generation down the line.

Part of the trick is that fear and xenophobia are self-perpetuating. In our ignorance, we fear strangers, so we try to keep them away, keep them out, learn nothing about them (just witness the furor that shut down an entire Virginia school district over an Arabic language assignment). And because we know nothing about them, we continue to see them as a strange, foreign, menacing other, who can readily be cast in a villainous role in the latest racist shadow-play. It’s a tactic that atheists have been the targets of often enough that we should be able to recognize it for what it is.

How can it be that we put so much importance on borders? These imaginary, invisible lines that we draw to divide us from others, that we think we can fortify with walls and gates and guns – they represent nothing inherent in the world. Nor do they protect us from danger, no matter what fools-gold promises politicians and pundits may utter. If you think you can shut out badness, isolate it, quarantine it, you’re living a fantasy. We can never make ourselves safe, secure or prosperous through mere subtraction.

No matter who you allow within your borders, there will always be good people and evildoers, the dependable and the untrustworthy, the diligent and the selfish. Those traits aren’t exemplified by certain national groups, they’re alloyed in every human being. What makes a country great has nothing to do with the ethnic or religious makeup of its people, but whether it embodies the spirit of mutual trust that births dynamism and achievement – and there’s no better test of trust than openness to immigrants.

Granted, I don’t expect dollars-and-cents arguments to sway minds in the grip of irrational fear. But there’s a deeper, moral argument with which to combat this phobia.

We haven’t all been refugees, but we have all been strangers at one time in our lives. Almost all of us have had a new home, a new school, a new city. Some of us in addition have had the experiences of a new family, a new country, a new flag. Except for a tiny and privileged few, we’ve all had times when we were dependent on the hospitality of others. If we were fortunate enough to receive it, we should remember those feelings of warmth and gratitude. If we were denied it, empathy should lead us to desire that others be spared that same rejection. It won’t even be a burden on us: we’re rich and strong, and we can afford to be generous.

Hospitality is as old as humanity. Especially during the solstice season, the glow of the hearth and the bread on the table have always stood for the promise of comfort and shelter from dark nights and cold weather. It’s both obligation and benediction. We offer welcome to our guests so that others will do the same for us, but in making the offer, we learn and strengthen our own capability for goodness. Like the fear it replaces, the virtue of openness is self-perpetuating. It’s the surest way to become the better people we aspire to be, and to stand proudly in the gaze of history that’s even now upon us.

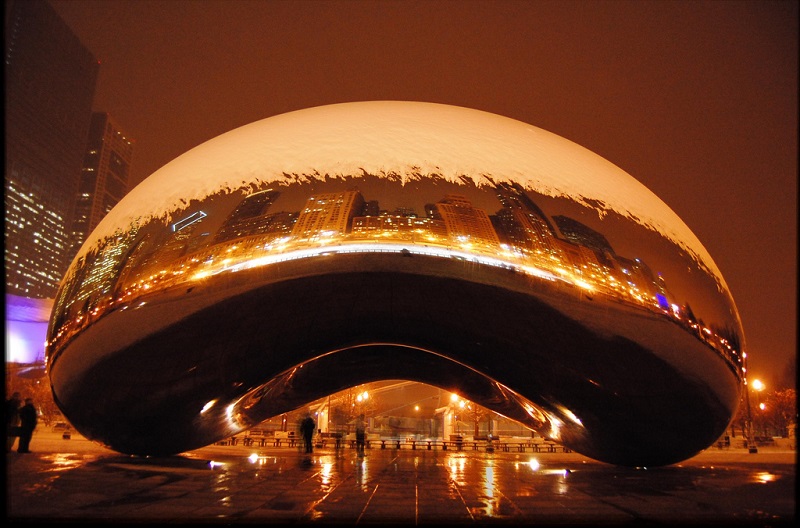

Image credit: Mike Warot, released under CC BY 2.0 license